* Commercial mold remediation

Crawlspace & Basement Mold Removal — Patriot Water Damage & Restoration

No content

* Commercial mold remediation Mold Remediation Service Near Me — Patriot Water Damage & Restoration .

No content

* Commercial mold remediation Mold Remediation Service Near Me — Patriot Water Damage & Restoration .

| Broken Arrow Public Schools | |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| United States | |

| District information | |

| Type | Public, Primary, Secondary |

| Established | 1904 |

| Schools | 28 |

| Students and staff | |

| Students | 20,000+ |

| Athletic conference | 6A |

| Other information | |

| Website | www |

Broken Arrow Public Schools (BAPS) is a public school district in Broken Arrow, Oklahoma. It was established in 1904. The district resides in an urban-suburban community with nearby agricultural areas and a growing business and industrial base. Serving more than 20,000 students, BAPS has four early childhood centers (Pre-K), 16 elementary schools (grades K-5), five middle schools (grades 6–8), one freshman academy (ninth grade), one high school (grades 10–12), one Options Academy, Virtual Academy, Vanguard Academy and Early College High School.[1][2]

Broken Arrow High School and the Freshman Academy are fully accredited by the state of Oklahoma and the North Central Association of Secondary Schools and Colleges.

Most of the district is in Tulsa County, where it includes most of Broken Arrow and a portion of Tulsa.[3] It extends into Wagoner County, where it includes all of that county's portion of Broken Arrow, a part of that county's part of Tulsa, and a portion of Coweta.[4]

|

Tulsa County

|

|

|---|---|

Tulsa County Courthouse

|

|

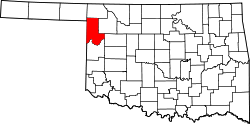

Location within the U.S. state of Oklahoma

|

|

Oklahoma's location within the U.S.

|

|

| Coordinates: 36°07′N 95°56′W / 36.12°N 95.94°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1907 |

| Named after | city of Tulsa |

| Seat | Tulsa |

| Largest city | Tulsa |

| Area

|

|

|

• Total

|

587 sq mi (1,520 km2) |

| • Land | 570 sq mi (1,500 km2) |

| • Water | 17 sq mi (44 km2) 2.9% |

| Population

(2020)

|

|

|

• Total

|

669,279 |

|

• Estimate

(2024)

|

693,514 |

| • Density | 1,216.7/sq mi (469.8/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional district | 1st |

| Website | www |

Tulsa County is a county located in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of the 2020 census, the population was 669,279,[1] making it the second-most populous county in the state, behind only Oklahoma County. Its county seat and largest city is Tulsa, the second-largest city in the state.[2] Founded at statehood, in 1907, it was named after the previously established city of Tulsa. Before statehood, the area was part of both the Creek Nation and the Cooweescoowee District of Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory. Tulsa County is included in the Tulsa metropolitan statistical area. Tulsa County is notable for being the most densely populated county in the state. Tulsa County also ranks as having the highest income.[3]

The history of Tulsa County greatly overlaps the history of the city of Tulsa. This section addresses events that largely occurred outside the present city limits of Tulsa.

The Lasley Vore Site, along the Arkansas River south of Tulsa, was claimed by University of Tulsa anthropologist George Odell to be the most likely place where Jean-Baptiste Bénard de la Harpe first encountered a group of Wichita people in 1719. Odell's statement was based on finding both Wichita and French artifacts there during an architectural dig in 1988.

The U. S. Government's removal of Native American tribes from the southeastern United States to "Indian Territory" did not take into account how that would impact the lives and attitudes of the nomadic tribes that already used the same land as their hunting grounds. At first, Creek immigrants stayed close to Fort Gibson, near the confluence of the Arkansas and Verdigris rivers. However, the government encouraged newer immigrants to move farther up the Arkansas. The Osage tribe had agreed to leave the land near the Verdigris, but had not moved far and soon threatened the new Creek settlements.[4]

In 1831, a party led by Rev. Isaac McCoy and Lt. James L. Dawson blazed a trail up the north side of the Arkansas from Fort Gibson to its junction with the Cimarron River. In 1832, Dawson was sent again to select sites for military posts. One of his recommended sites was about two and a half miles downstream from the Cimarron River junction. The following year, Brevet Major George Birch and two companies of the 7th Infantry Regiment followed the "Dawson Road" to the aforementioned site. Flattering his former commanding officer, General Matthew Arbuckle, Birch named the site "Fort Arbuckle."[4][5]

According to Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, the fort was about 8 miles (13 km) west of the present city of Sand Springs, Oklahoma.[6] Author James Gardner visited the site in the early 1930s. His article describing the visit includes an old map showing the fort located on the north bank of the Arkansas River near Sand Creek, just south of the line separating Tulsa County and Osage County. After ground was cleared and a blockhouse built, Fort Arbuckle was abandoned November 11, 1834. The remnants of stockade and some chimneys could still be seen nearly a hundred years later.[5] The site was submerged when Keystone Lake was built.

Main article Battle of Chusto-Talasah

At the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, many Creeks and Seminoles in Indian Territory, led by Opothleyahola, retained their allegiance to the U. S. Government. In November 1861, Confederate Col. Douglas H. Cooper led a Confederate force against the Union supporters with the purpose of either compelling their submission or driving them out of the country. The first clash, known as the Battle of Round Mountain, occurred November 19, 1861. Although the Unionists successfully withstood the attack and mounted a counterattack, the Confederates claimed a strategic victory because the Unionists were forced to withdraw.[7]

The next battle occurred December 9, 1861. Col. Cooper's force attacked the Unionists at Chusto-Talasah (Caving Banks) on the Horseshoe Bend of Bird Creek in what is now Tulsa County. The Confederates drove the Unionists across Bird Creek, but could not pursue, because they were short of ammunition. Still, the Confederates could claim victory.[7]

The Atlantic and Pacific Railroad had extended its main line in Indian Territory from Vinita to Tulsa in 1883, where it stopped on the east side of the Arkansas River. The company, which later merged into the St. Louis and San Francisco Railway (familiarly known as the Frisco), then built a steel bridge across the river to extend the line to Red Fork. This bridge allowed cattlemen to load their animals onto the railroad west of the Arkansas instead of fording the river, as had been the practice previously. It also provided a safer and more convenient way to bring workers from Tulsa to the oil field after the 1901 discovery of oil in Red Fork.

A wildcat well named Sue Bland No. 1 hit paydirt at 540 feet on June 25, 1901, as a gusher. The well was on the property of Sue A. Bland (née Davis), located near the community of Red Fork. Mrs. Bland was a Creek citizen and wife of Dr. John C. W. Bland, the first practicing physician in Tulsa. The property was Mrs. Bland's homestead allotment. Oil produced by the well was shipped in barrels to the nearest refinery in Kansas, where it was sold for $1.00 a barrel.[8]

Other producing wells followed soon after. The next big strike in Tulsa County was the Glenn Pool Oil Reserve in the vicinity of where Glenpool, Oklahoma was later founded..

Ironically, while the city of Tulsa claimed to be "Oil Capital of the World" for much of the 20th century, a city ordinance banned drilling for oil within the city limits.

In 1911–1912, Tulsa County built a court house in Tulsa on the northeast corner of Sixth Street and South Boulder Avenue. Yule marble was used in its construction. The land had previously been the site of a mansion owned by George Perryman and his wife. This was the court house where a mob of white residents gathered on May 31, 1921, threatening to lynch a young black man held in the top-floor jail. It was the beginning of the Tulsa Race Massacre.

An advertisement for bids specified that the building should be fireproof, built of either reinforced concrete or steel and concrete. The size was to be 120 by 120 feet (37 by 37 m) with three floors and a full basement. Cost of the building was not to exceed $200,000. The jail on the top floor was not to exceed $25,000.[9]

The building continued to serve until the present court house building (shown above) opened at 515 South Denver. The old building was then demolished and the land was sold to private investors. The land is now the site of the Bank of America building, completed in 1967.

In the early 20th century, Tulsa was home to the "Black Wall Street", one of the most prosperous Black communities in the United States at the time.[10] Located in the Greenwood neighborhood, it was the site of the Tulsa Race Massacre, said to be "the single worst incident of racial violence in American history",[11] in which mobs of white Tulsans killed black Tulsans, looted and robbed the black community, and burned down homes and businesses.[10] Sixteen hours of massacring on May 31 and June 1, 1921, ended only when National Guardsmen were brought in by the Governor. An official report later claimed that 23 Black and 16 white citizens were killed, but other estimates suggest as many as 300 people died, most of them Black.[10] Over 800 people were admitted to local hospitals with injuries, and an estimated 1000 Black people were left homeless as 35 city blocks, composed of 1,256 residences, were destroyed by fire. Property damage was estimated at $1.8 million.[10] Efforts to obtain reparations for survivors of the violence have been unsuccessful, but the events were re-examined by the city and state in the early 21st century, acknowledging the terrible actions that had taken place.[12]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 587 square miles (1,520 km2), of which 570 square miles (1,500 km2) is land and 17 square miles (44 km2) (2.9%) is water.[13]

The Arkansas River drains most of the county. Keystone Lake, formed by a dam on the Arkansas River, lies partially in the county. Bird Creek and the Caney River, tributaries of the Verdigris River drain the northern part of the county.[6]

| Monthly Normal and Record High and Low Temperatures | ||||||||||||

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rec High °F | 79 | 90 | 96 | 102 | 96 | 103 | 112 | 110 | 109 | 98 | 87 | 80 |

| Norm High °F | 46.5 | 52.9 | 62.4 | 72.1 | 79.6 | 88 | 93.8 | 93.2 | 84.1 | 74 | 60 | 49.6 |

| Norm Low °F | 26.3 | 31.1 | 40.3 | 49.5 | 59 | 67.9 | 73.1 | 71.2 | 62.9 | 51.1 | 39.3 | 29.8 |

| Rec Low °F | -8 | -11 | -3 | 22 | 35 | 49 | 51 | 52 | 35 | 18 | 10 | -8 |

| Precip (in) | 1.6 | 1.95 | 3.57 | 3.95 | 6.11 | 4.72 | 2.96 | 2.85 | 4.76 | 4.05 | 3.47 | 2.43 |

| Source: USTravelWeather.com [3] | ||||||||||||

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1910 | 34,995 | — | |

| 1920 | 109,023 | 211.5% | |

| 1930 | 187,574 | 72.0% | |

| 1940 | 193,363 | 3.1% | |

| 1950 | 251,686 | 30.2% | |

| 1960 | 346,038 | 37.5% | |

| 1970 | 401,663 | 16.1% | |

| 1980 | 470,593 | 17.2% | |

| 1990 | 503,341 | 7.0% | |

| 2000 | 563,299 | 11.9% | |

| 2010 | 603,403 | 7.1% | |

| 2020 | 669,279 | 10.9% | |

| 2024 (est.) | 693,514 | [14] | 3.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[15] 1790-1960[16] 1900-1990[17] 1990-2000[18] 2010-2019[1] |

|||

At the census of 2010,[19] there were 603,403 people, 241,737 households, and 154,084 families residing in the county. The population density was 1,059 inhabitants per square mile (409/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 69.2% White, 10.7% Black or African American, 6.0% Native American, 2.3% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 5.8% from other races, and 5.8% from two or more races. 11.0% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race (8.8% Mexican). 14.2% were of German, 12.3% Irish, 8.8% English, 8.5% American, 2.3% French, and 2.3% Scottish ancestries. 88.3% spoke English, 8.1% Spanish, and 0.4% Vietnamese as their first language.[20][21] At the 2020 census, its population grew to 669,279 people; in 2022, the American Community Survey estimated its population was 677,358. The 2021 estimated racial makeup of the county was 59.9% non-Hispanic white, 10.8% African American, 7.3% Native American, 3.8% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 6.6% multiracial, and 13.9% Hispanic or Latino of any race.[22]

As of 2010, there were 241,737 households, out of which 30.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.3% were married couples living together, 13.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.3% were non-families. 29.60% of all households were made up of individuals, and 22% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.46 and the average family size was 3.07. In 2021, there were 295,350 households with a median house value of $168,800. The county had a median rent of $929.[22]

As of 2010 in the county, the population was spread out, with 26.30% under the age of 18, 10.00% from 18 to 24, 30.40% from 25 to 44, 21.60% from 45 to 64, and 11.80% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.20 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.90 males.

As of 2010, the median income for a household in the county was $47,005, and the median income for a family was $60,093. The per capita income for the county was $27,425. About 11.0% of families and 15.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 22.6% of those under age 18 and 8.2% of those age 65 or over.[23][24] Of the county's population over the age of 25, 29.2% held a bachelor's degree or higher, and 88.2% have a high school diploma or equivalent. As of 2021, its median household income was $60,382 and 14.7% of the population lived at or below the poverty line.[22]

Tulsa County has nine elected county officials: three county commissioners, a county sheriff, a district attorney, an assessor, a treasurer, a county clerk, and a county court clerk.[25]

| Position | Official | First Elected | Next Re-election Year | Party |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| County Commissioner District 1 | Stan Sallee | 2018 | 2026 | Rep |

| County Commissioner District 2 | Lonnie Sims | 2024 | 2028 | Rep |

| County Commissioner District 3 | Kelly Dunkerley | 2023 | 2026 | Rep |

| District Attorney | Steve Kunzweiler | 2015 | 2026 | Rep |

| County Assessor | John A. Wright | 2018 | 2026 | Rep |

| County Clerk | Michael Willis | 2017 | 2028 | Rep |

| County Court Clerk | Don Newberry | 2017 | 2028 | Rep |

| County Sheriff | Vic Regalado | 2017 | 2028 | Rep |

| County Treasurer | John Fothergill | 2020 | 2026 | Rep |

Oklahoma's 14th Judicial District, which includes Tulsa and Pawnee County, has 14 elected district judges. 13 of the judges are elected from Tulsa County.[26] The one elected Associate Judge for Tulsa County is Cliff Smith of Tulsa.[27]

| Position | Official | First Elected | Next Re-election Year | Hometown |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Office 1 | Caroline Wall | 2010 | 2026 | Tulsa |

| Office 2 | Sharron Holmes | 2014 | 2026 | Tulsa |

| Office 3 | Tracy Priddy | 2018 | 2026 | Tulsa |

| Office 4 | Daman H. Cantrell | 1998 | 2026 | Owasso |

| Office 5 (Pawnee County) | Michelle L. Bodine-Keely | 2020 | 2026 | Cleveland |

| Office 6 | Kelly Greenough | 2016 | 2026 | Tulsa |

| Office 7 | William LaFortune | 2014 | 2026 | Tulsa |

| Office 8 | Doug Drummond | 2014 | 2026 | Tulsa |

| Office 9 | Richard L. Hathcoat | 2023[28] | 2026 | Tulsa |

| Office 10 | Dawn Moody | 2018 | 2026 | Tulsa |

| Office 11 | Rebecca Nightingale | 2002 | 2026 | Tulsa |

| Office 12 | Kevin Gray | 2022 | 2026 | Tulsa |

| Office 13 | David Guten[29] | 2022 | 2026 | Tulsa |

| Office 14 | Kurt G. Glassco | 2009 | 2026 | Tulsa |

Tulsa County is very conservative for an urban county; it has voted Republican in every presidential election since 1940.[30] The county's Republican bent predates Oklahoma's swing toward the GOP.

George H. W. Bush in 1992 remains the only Republican since Alf Landon in 1936 to fail to obtain a majority in the county, and even then only because of Ross Perot’s strong third-party candidacy.

In 2020, Joe Biden became the first Democrat since Lyndon Johnson in 1964 to win more than 40% of the vote in Tulsa County, and only the second to do so since 1948. It is one of only two counties in the state, alongside Oklahoma County, where Biden outperformed Southerner Jimmy Carter's 1976 margin, when he narrowly lost the state.

In 2022, Democratic gubernatorial candidate (and county resident) Joy Hofmeister narrowly carried the county, 49.1-48.9, against incumbent Republican Kevin Stitt.[31] This was the first time Tulsa County had backed a Democratic gubernatorial candidate since 2006, and the first time in its history that it had ever backed a losing Democrat for governor.[32]

In 2024, Democratic nominee Kamala Harris won 41.3% of the vote in the county, the highest vote share since 1964. The county swung towards Democrats by less than 1 percentage point from 2020 to 2024. The county still remained strongly Republican.

The city of Tulsa is consistently conservative and regularly votes Republican in presidential and other statewide races. In recent years, this advantage has considerably narrowed. Its urban core is a swing region. After voting for Donald Trump in 2016 by four points, it swung to a six-point win for Joe Biden in 2020, and also backed Drew Edmondson for Governor in 2018 by 13 points. The rest of the city, however, remains very strongly Republican.[33][34][35][36]

In February 2020, registered Republicans were reduced from a majority to a plurality in the county's voter registration.[37]

| Voter registration and party enrollment as of January 15, 2025[38] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of Voters | Percentage | |||

| Republican | 195,133 | 47.96% | |||

| Democratic | 119,120 | 29.29% | |||

| Libertarian | 4,207 | 1.03% | |||

| Unaffiliated | 88,390 | 21.72% | |||

| Total | 406,850 | 100% | |||

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 1908 | 2,150 | 46.04% | 2,292 | 49.08% | 228 | 4.88% |

| 1912 | 2,029 | 37.95% | 2,747 | 51.37% | 571 | 10.68% |

| 1916 | 3,857 | 41.74% | 4,497 | 48.67% | 886 | 9.59% |

| 1920 | 14,357 | 57.43% | 10,025 | 40.10% | 617 | 2.47% |

| 1924 | 19,537 | 55.54% | 14,377 | 40.87% | 1,265 | 3.60% |

| 1928 | 38,769 | 70.49% | 16,062 | 29.20% | 167 | 0.30% |

| 1932 | 25,541 | 41.96% | 35,330 | 58.04% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1936 | 28,759 | 40.88% | 41,256 | 58.65% | 328 | 0.47% |

| 1940 | 40,342 | 54.83% | 33,098 | 44.99% | 135 | 0.18% |

| 1944 | 42,663 | 56.00% | 33,436 | 43.89% | 89 | 0.12% |

| 1948 | 42,892 | 52.67% | 38,548 | 47.33% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1952 | 73,862 | 61.25% | 46,728 | 38.75% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1956 | 83,219 | 65.51% | 43,805 | 34.49% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 89,899 | 63.03% | 52,725 | 36.97% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1964 | 76,770 | 55.53% | 61,484 | 44.47% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1968 | 81,476 | 57.11% | 32,748 | 22.95% | 28,443 | 19.94% |

| 1972 | 125,278 | 77.75% | 32,779 | 20.34% | 3,069 | 1.90% |

| 1976 | 108,653 | 61.63% | 65,298 | 37.04% | 2,349 | 1.33% |

| 1980 | 124,643 | 66.25% | 53,438 | 28.40% | 10,067 | 5.35% |

| 1984 | 159,549 | 72.90% | 58,274 | 26.62% | 1,049 | 0.48% |

| 1988 | 127,512 | 64.48% | 69,044 | 34.91% | 1,207 | 0.61% |

| 1992 | 117,465 | 49.13% | 71,165 | 29.77% | 50,438 | 21.10% |

| 1996 | 111,243 | 53.65% | 76,924 | 37.10% | 19,189 | 9.25% |

| 2000 | 134,152 | 61.34% | 81,656 | 37.34% | 2,883 | 1.32% |

| 2004 | 163,452 | 64.43% | 90,220 | 35.57% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 2008 | 158,363 | 62.23% | 96,133 | 37.77% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 2012 | 145,062 | 63.68% | 82,744 | 36.32% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 2016 | 144,258 | 58.39% | 87,847 | 35.56% | 14,949 | 6.05% |

| 2020 | 150,574 | 56.46% | 108,996 | 40.87% | 7,108 | 2.67% |

| 2024 | 145,241 | 56.53% | 106,105 | 41.30% | 5,593 | 2.18% |

River Parks was established in 1974 as a joint operation of the City of Tulsa and Tulsa County, with funding from both governments as well as private entities. It is not a part of the Tulsa Parks and Recreation Department, but is managed by the River Parks Authority. It is a series of linear parks that run adjacent to the Arkansas River for about 10 miles (16 km) from downtown to the Jenks bridge. Since 2007 a significant portion of the River Parks area has been renovated with new trails, landscaping and playground equipment. The River Parks Turkey Mountain Urban Wilderness Area on the west side of the Arkansas River in south Tulsa is a 300 acres (120 ha) area that contains over 45 miles (72 km) of dirt trails available for hiking, trail running, mountain biking and horseback riding.[40] The "Tulsa Townies" organization provide bicycles that may be checked out for use. There are three kiosks in the parks where bicycles may be obtained or returned.[41]

Public school districts include:[48]

Public institutions:

Private institutions:

The following sites in Tulsa County are listed on the National Register of Historic Places:

36°07′N 95°56′W / 36.12°N 95.94°W

Coordinates: 35°28′7″N 97°31′17″W / 35.46861°N 97.52139°WCountryUnited StatesStateOklahomaCounties

FoundedApril 22, 1889[3]IncorporatedJuly 15, 1890[3]Government

• TypeCouncil–manager • BodyOklahoma City Council • MayorDavid Holt (R) • City managerCraig FreemanArea

620.79 sq mi (1,607.83 km2) • Land606.48 sq mi (1,570.77 km2) • Water14.31 sq mi (37.06 km2) • Urban

421.7 sq mi (1,092.3 km2)Elevation

1,198 ft (365 m)Population

681,054

712,919 ![]() • Rank62nd in North America

• Rank62nd in North America

20th in the United States

1st in Oklahoma • Density1,123.0/sq mi (433.58/km2) • Urban

982,276 (US: 46th) • Urban density2,329/sq mi (899.3/km2) • Metro

1,497,821 (US: 42nd)

Demonyms

GDP

• Metro$100.054 billion (2023)Time zoneUTC−6 (Central (CST)) • Summer (DST)UTC−5 (CDT)ZIP Codes

Area codes405/572FIPS code40-55000GNIS feature ID1102140[5]Websiteokc.gov

Oklahoma City (/ˌoʊkləˈhoʊmə -/ ⓘ OH-klə-HOH-mə -), often shortened to OKC, is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Oklahoma. It is the 20th-most populous U.S. city and 8th largest in the Southern United States with a population of 681,054 at the 2020 census,[10] while the Oklahoma City metropolitan area with an estimated 1.49 million residents is the largest metropolitan area in the state and 42nd-most populous in the nation.[11] It is the county seat of Oklahoma County,[12] with the city limits extending into Canadian, Cleveland, and Pottawatomie counties; however, areas beyond Oklahoma County primarily consist of suburban developments or areas designated rural and watershed zones. Oklahoma City ranks as the tenth-largest city by area in the United States when including consolidated city-counties, and second-largest when such consolidations are excluded. It is also the second-largest state capital by area, following Juneau, Alaska.

Oklahoma City has one of the world's largest livestock markets.[13] Oil, natural gas, petroleum products, and related industries are its economy's largest sector. The city is in the middle of an active oil field, and oil derricks dot the capitol grounds. The federal government employs a large number of workers at Tinker Air Force Base and the United States Department of Transportation's Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center (which house offices of the Federal Aviation Administration and the Transportation Department's Enterprise Service Center, respectively).

Oklahoma City is on the I-35 and I-40 corridors, one of the primary travel corridors south into neighboring Texas and New Mexico, north towards Wichita and Kansas City, west to Albuquerque, and east towards Little Rock and Memphis. Located in the state's Frontier Country region, the city's northeast section lies in an ecological region known as the Cross Timbers. The city was founded during the Land Run of 1889 and grew to a population of over 10,000 within hours of its founding. It was the site of the April 19, 1995, bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, in which 168 people died.[14]

Since weather records have been kept beginning in 1890, Oklahoma City has been struck by 13 violent tornadoes, 11 of which were rated F4 or EF4 on the Fujita and Enhanced Fujita scales, and two rated F5 and EF5.[15]

| Native American names for Oklahoma City |

| Choctaw: Tʋmaha chito Oklahumma |

| Cherokee: ᎣᎦᎳᎰᎹ ᎦᏚᎲᎢ |

| Romanized: ogalahoma gaduhvi |

| Cheyenne: Ma'xepóno'e |

| Comanche: Pia Sooka̠hni |

| Delaware: Oklahoma-utènaii |

| Iowa-Oto: Chína Chége Itúⁿ[16] |

| Meskwaki: Okonohômîheki[17] |

| Navajo: Halgai Hóteeldi Kin Haalʼáhí |

Oklahoma City was settled on April 22, 1889,[18] when the area known as the "Unassigned Lands" was opened for settlement in an event known as "The Land Run".[19] On April 26 of that year, its first mayor was elected, William Couch. Some 10,000 homesteaders settled in the area that would become the capital of Oklahoma. The town grew quickly; the population doubled between 1890 and 1900.[20] Early leaders of the development of the city included Anton H. Classen, John Wilford Shartel, Henry Overholser, Oscar Ameringer, Jack C. Walton, Angelo C. Scott, and James W. Maney.

By the time Oklahoma was admitted to the Union in 1907, Oklahoma City had surpassed Guthrie, the territorial capital, as the new state's population center and commercial hub. Soon after, the capital was moved from Guthrie to Oklahoma City.[21] Oklahoma City was a significant stop on U.S. Route 66 during the early part of the 20th century; it was prominently mentioned in Bobby Troup's 1946 jazz song "(Get Your Kicks on) Route 66" made famous by artist Nat King Cole.

Before World War II, Oklahoma City developed significant stockyards, attracting jobs and revenue formerly in Chicago and Omaha, Nebraska. With the 1928 discovery of oil within the city limits (including under the State Capitol), Oklahoma City became a major center of oil production.[22] Post-war growth accompanied the construction of the Interstate Highway System, which made Oklahoma City a major interchange as the convergence of I-35, I-40, and I-44. It was also aided by the federal development of Tinker Air Force Base after successful lobbying efforts by the director of the Chamber of Commerce Stanley Draper.

In 1950, the Census Bureau reported the city's population as 8.6% black and 90.7% white.[23]

In 1959, the city government launched a "Great Annexation Drive" that expanded the city's area from 80 to 475.55 square miles (207.2 to 1,231.7 square kilometers) by the end of 1961, making it the largest U.S. city by land mass at the time.[24]

Patience Latting was elected Mayor of Oklahoma City in 1971, becoming the city's first female mayor.[25] Latting was also the first woman to serve as mayor of a U.S. city with over 350,000 residents.[25]

Like many other American cities, the center city population declined in the 1970s and 1980s as families followed newly constructed highways to move to newer housing in nearby suburbs. Urban renewal projects in the 1970s, including the Pei Plan, removed older structures but failed to spark much new development, leaving the city dotted with vacant lots used for parking. A notable exception was the city's construction of the Myriad Gardens and Crystal Bridge, a botanical garden and modernistic conservatory in the heart of downtown. Architecturally significant historic buildings lost to clearances were the Criterion Theater,[26][27] the Baum Building,[28] the Hales Building,[29][30] and the Biltmore Hotel.[31]

In 1993, the city passed a massive redevelopment package known as the Metropolitan Area Projects (MAPS), intended to rebuild the city's core with civic projects to establish more activities and life in downtown. The city added a new baseball park; a central library; renovations to the civic center, convention center, and fairgrounds; and a water canal in the Bricktown entertainment district. Water taxis transport passengers within the district, adding color and activity along the canal. MAPS has become one of the most successful public-private partnerships undertaken in the U.S., exceeding $3 billion in private investment as of 2010.[32] As a result of MAPS, the population in downtown housing has exponentially increased, with the demand for additional residential and retail amenities, such as groceries, services, and shops.

Since the completion of the MAPS projects, the downtown area has seen continued development. Several downtown buildings are undergoing renovation/restoration. Notable among these was the restoration of the Skirvin Hotel in 2007. The famed First National Center is also being renovated.

Residents of Oklahoma City suffered substantial losses on April 19, 1995, when Timothy McVeigh detonated a bomb in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building. The building was destroyed (the remnants of which had to be imploded in a controlled demolition later that year), more than 100 nearby buildings suffered severe damage, and 168 people were killed,[33] making it the deadliest act of domestic terrorism in U.S. history.[34] The site of the Murrah Building has been commemorated as the Oklahoma City National Memorial and Museum.[35] Since its opening in 2000, over three million people have visited.[citation needed]

The "Core-to-Shore" project was created to relocate I-40 one mile (1.6 km) south and replace it with a boulevard to create a landscaped entrance to the city.[36] This also allows the central portion of the city to expand south and connect with the shore of the Oklahoma River. Several elements of "Core to Shore" were included in the MAPS 3 proposal approved by voters in late 2009.

In 2012, Devon Energy completed the construction of their new skyscraper, the Devon Energy Center, which immediately became the tallest building in Oklahoma City as well as the state of Oklahoma at 844 feet (257.25m). Culturally, the “Devon Tower”, as it is called by locals,[37] has been considered the centerpiece of the city’s skyline. Mayor Mick Cornett attended the building’s opening ceremony and stated, "The visual impact it has on the city is so striking and so identifiable. It took just over three years to complete the building that has quickly become a staple in our city's skyline."[38]

Oklahoma City is set to become the home of the Legends Tower, which when complete would be the tallest building in the United States and amongst the tallest buildings in the world.[39]

Oklahoma City lies along one of the primary corridors into Texas and Mexico and is a three-hour drive from the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex. The city is in the Frontier Country region in the state's center, making it ideal for state government.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 620.79 square miles (1,607.8 km2),[40] of which 601.11 square miles (1,556.9 km2) is land and 19.23 square miles (49.8 km2) is water. The city has annexed 480 net acres under the leadership of Mayor David Holt.

Oklahoma City lies in the Sandstone Hills region of Oklahoma, known for hills of 250 to 400 feet (80 to 120 m) and two species of oak: blackjack oak (Quercus marilandica) and post oak (Q. stellata).[41] The northeastern part of the city and its eastern suburbs fall into an ecological region known as the Cross Timbers.[42]

The city is roughly bisected by the North Canadian River (recently renamed the Oklahoma River inside city limits). The North Canadian once had sufficient flow to flood every year, wreaking destruction on surrounding areas, including the central business district and the original Oklahoma City Zoo.[43] In the 1940s, a dam was built on the river to manage the flood control and reduce its level.[44] In the 1990s, as part of the citywide revitalization project known as MAPS, the city built a series of low-water dams, returning water to the portion of the river flowing near downtown.[45] The city has three large lakes: Lake Hefner and Lake Overholser, in the northwestern quarter of the city; and the largest, Lake Stanley Draper, in the city's sparsely populated far southeast portion.

The population density typically reported for Oklahoma City using the area of its city limits can be misleading. Its urbanized zone covers roughly 244 square miles (630 km2) resulting in a 2013 estimated density of 2,500 per square mile (970/km2), compared with larger rural watershed areas incorporated by the city, which cover the remaining 377 sq mi (980 km2) of the city limits.[46]

Oklahoma City is one of the largest cities in the nation in compliance with the Clean Air Act.[47]

| Rank | Building | Height | Floors | Built | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Devon Energy Center | 844 feet (257 m) | 50 | 2012 | [48] |

| 2 | BancFirst Tower | 500 feet (152 m) | 36 | 1971 | [49] |

| 3 | First National Center | 446 feet (136 m) | 33 | 1931 | [50] |

| 4 | BOK Park Plaza | 433 feet (132 m) | 27 | 2017 | [51] |

| 5 | Oklahoma Tower | 410 feet (125 m) | 31 | 1982 | [52] |

| 6 | Strata Tower | 393 feet (120 m) | 30 | 1973 | [53] |

| 7 | City Place | 391 feet (119 m) | 33 | 1931 | [54] |

| 8 | Valliance Bank Tower | 321 feet (98 m) | 22 | 1984 | [55] |

| 9 | Leadership Square North | 285 feet (87 m) | 22 | 1984 | [56] |

| 10 | Arvest Tower | 281 feet (86 m) | 16 | 1972 | [57] |

Oklahoma City neighborhoods are highly varied, with affluent historic neighborhoods located next to districts that have not wholly recovered from the economic and social decline of the 1970s and 1980s.[citation needed]

The city is bisected geographically and culturally by the North Canadian River, which divides North Oklahoma City and South Oklahoma City. The north side is characterized by diverse and fashionable urban neighborhoods near the city center and sprawling suburbs further north. South Oklahoma City is generally more blue-collar working class and significantly more industrial, having grown up around the Stockyards and meat packing plants at the turn of the century. It is also the center of the city's rapidly growing Latino community.

Downtown Oklahoma City, which has 7,600 residents, is seeing an influx of new private investment and large-scale public works projects, which have helped to revitalize a central business district left almost deserted by the Oil Bust of the early 1980s. The centerpiece of downtown is the newly renovated Crystal Bridge and Myriad Botanical Gardens, one of the few elements of the Pei Plan to be completed. In 2021, a massive new central park will link the gardens near the CBD and the new convention center to be built just south of it to the North Canadian River as part of a massive works project known as "Core to Shore"; the new park is part of MAPS3, a collection of civic projects funded by a one-cent temporary (seven-year) sales tax increase.[58]

Oklahoma City has a temperate humid subtropical climate (Köppen: Cfa, Trewartha: Cfak), along with significant continental influences. The city features hot, humid summers and cool winters. Prolonged and severe droughts (sometimes leading to wildfires in the vicinity) and hefty rainfall leading to flash flooding and flooding occur regularly. Consistent winds, usually from the south or south-southeast during the summer, help temper the hotter weather. Consistent northerly winds during the winter can intensify cold periods. Severe ice storms and snowstorms happen sporadically during the winter.

The average temperature is 61.4 °F (16.3 °C), with the monthly daily average ranging from 39.2 °F (4.0 °C) in January to 83.0 °F (28.3 °C) in July. Extremes range from −17 °F (−27 °C) on February 12, 1899 to 113 °F (45 °C) on August 11, 1936, and August 3, 2012;[59] The last sub-zero (Fahrenheit) reading was −14 °F (−26 °C) on February 16, 2021.[60][61] Temperatures reach 100 °F (38 °C) on 10.4 days of the year, 90 °F (32 °C) on nearly 70 days, and fail to rise above freezing on 8.3 days.[60] The city receives about 35.9 inches (91.2 cm) of precipitation annually, of which 8.6 inches (21.8 cm) is snow.

The report "Regional Climate Trends and Scenarios for the U.S. National Climate Assessment" (NCA) from 2013 by NOAA projects that parts of the Great Plains region can expect up to 30% (high emissions scenario based on CMIP3 and NARCCAP models) increase in extreme precipitation days by mid-century. This definition is based on days receiving more than one inch of rainfall.[62]

Oklahoma City has an active severe weather season from March through June, especially during April and May. Being in the center of what is colloquially referred to as Tornado Alley, it is prone to widespread and severe tornadoes, as well as severe hailstorms and occasional derechoes. Tornadoes occur every month of the year, and a secondary smaller peak also occurs during autumn, especially in October. The Oklahoma City metropolitan area is one of the most tornado-prone major cities in the world, with about 150 tornadoes striking within the city limits since 1890. Since the time weather records have been kept, Oklahoma City has been struck by 13 violent tornadoes, eleven rated F/EF4 and two rated F/EF5.[15]

On May 3, 1999, parts of Oklahoma City and surrounding communities were impacted by a tornado. It was the last U.S. tornado to be given a rating of F5 on the Fujita scale before the Enhanced Fujita scale replaced it in 2007. While the tornado was in the vicinity of Bridge Creek to the southwest, wind speeds of 318 mph (510 km/h) were estimated by a mobile Doppler radar, the highest wind speeds ever recorded on Earth.[63] A second top-of-the-scale tornado occurred on May 20, 2013; South Oklahoma City, along with Newcastle and Moore, was hit by an EF5 tornado. The tornado was 0.5 to 1.3 miles (0.80 to 2.09 km) wide and killed 23 people.[64] On May 31, less than two weeks after the May 20 event, another outbreak affected the Oklahoma City area. Within Oklahoma City, the system spawned an EF1 and an EF0 tornado, and in El Reno to the west, an EF3 tornado occurred. This lattermost tornado, which was heading in the direction of Oklahoma City before it dissipated, had a width of 2.6 miles (4.2 km), making it the widest tornado ever recorded. Additionally, winds over 295 mph (475 km/h) were measured, one of the two highest wind records for a tornado.[65]

With 19.48 inches (495 mm) of rainfall, May 2015 was Oklahoma City's record-wettest month since record-keeping began in 1890. Across Oklahoma and Texas generally, there was a record flooding in the latter part of the month.[66]

| Climate data for Oklahoma City (Will Rogers World Airport), 1991−2020 normals,[a] extremes 1890−present[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 83 (28) |

92 (33) |

97 (36) |

100 (38) |

104 (40) |

107 (42) |

110 (43) |

113 (45) |

108 (42) |

97 (36) |

87 (31) |

86 (30) |

113 (45) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 71.7 (22.1) |

77.1 (25.1) |

84.2 (29.0) |

86.9 (30.5) |

92.3 (33.5) |

96.4 (35.8) |

102.4 (39.1) |

101.5 (38.6) |

96.2 (35.7) |

88.9 (31.6) |

79.1 (26.2) |

71.2 (21.8) |

103.8 (39.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 49.3 (9.6) |

53.8 (12.1) |

62.9 (17.2) |

71.1 (21.7) |

78.9 (26.1) |

87.5 (30.8) |

93.1 (33.9) |

92.2 (33.4) |

83.9 (28.8) |

72.8 (22.7) |

60.7 (15.9) |

50.4 (10.2) |

71.4 (21.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 38.2 (3.4) |

42.3 (5.7) |

51.2 (10.7) |

59.3 (15.2) |

68.2 (20.1) |

76.9 (24.9) |

81.7 (27.6) |

80.7 (27.1) |

72.7 (22.6) |

61.1 (16.2) |

49.2 (9.6) |

40.0 (4.4) |

60.1 (15.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 27.0 (−2.8) |

30.8 (−0.7) |

39.5 (4.2) |

47.5 (8.6) |

57.6 (14.2) |

66.2 (19.0) |

70.3 (21.3) |

69.1 (20.6) |

61.5 (16.4) |

49.4 (9.7) |

37.7 (3.2) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

48.8 (9.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 11.7 (−11.3) |

15.4 (−9.2) |

21.5 (−5.8) |

32.3 (0.2) |

43.8 (6.6) |

56.6 (13.7) |

63.6 (17.6) |

61.7 (16.5) |

48.4 (9.1) |

33.8 (1.0) |

21.7 (−5.7) |

14.3 (−9.8) |

7.5 (−13.6) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −11 (−24) |

−17 (−27) |

1 (−17) |

20 (−7) |

32 (0) |

46 (8) |

53 (12) |

49 (9) |

35 (2) |

16 (−9) |

9 (−13) |

−8 (−22) |

−17 (−27) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.32 (34) |

1.42 (36) |

2.55 (65) |

3.60 (91) |

5.31 (135) |

4.49 (114) |

3.59 (91) |

3.60 (91) |

3.72 (94) |

3.32 (84) |

1.68 (43) |

1.79 (45) |

36.39 (924) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 1.8 (4.6) |

1.8 (4.6) |

0.8 (2.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.5 (1.3) |

1.8 (4.6) |

6.7 (17) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 5.0 | 5.7 | 6.9 | 7.9 | 10.0 | 8.6 | 6.0 | 6.7 | 7.1 | 7.5 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 82.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 4.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66.6 | 65.7 | 61.3 | 61.1 | 67.5 | 67.2 | 60.9 | 61.6 | 67.1 | 64.4 | 67.1 | 67.8 | 64.9 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 23.7 (−4.6) |

28.0 (−2.2) |

35.2 (1.8) |

45.1 (7.3) |

55.8 (13.2) |

63.7 (17.6) |

65.3 (18.5) |

64.4 (18.0) |

59.5 (15.3) |

47.7 (8.7) |

37.0 (2.8) |

27.5 (−2.5) |

46.1 (7.8) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 200.8 | 189.7 | 244.2 | 271.3 | 295.2 | 326.1 | 356.6 | 329.3 | 263.7 | 245.1 | 186.5 | 180.9 | 3,089.4 |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.1 | 10.9 | 12.0 | 13.1 | 14.1 | 14.5 | 14.3 | 13.4 | 12.4 | 11.3 | 10.3 | 9.8 | 12.2 |

| Percentage possible sunshine | 64 | 62 | 66 | 69 | 68 | 75 | 80 | 79 | 71 | 70 | 60 | 60 | 69 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 6.4 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961−1990)[67][60][68] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas(Daylight-UV) [69] | |||||||||||||

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 4,151 | — | |

| 1900 | 10,037 | 141.8% | |

| 1910 | 64,205 | 539.7% | |

| 1920 | 91,295 | 42.2% | |

| 1930 | 185,389 | 103.1% | |

| 1940 | 204,424 | 10.3% | |

| 1950 | 243,504 | 19.1% | |

| 1960 | 324,253 | 33.2% | |

| 1970 | 368,164 | 13.5% | |

| 1980 | 404,014 | 9.7% | |

| 1990 | 444,719 | 10.1% | |

| 2000 | 506,132 | 13.8% | |

| 2010 | 579,999 | 14.6% | |

| 2020 | 681,054 | 17.4% | |

| 2024 (est.) | 712,919 | [6] | 4.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[70] 1790-1960[71] 1900-1990[72] 1990-2000[73] 2010[74] |

|||

In the 2010 census, there were 579,999 people, 230,233 households, and 144,120 families in the city. The population density was 956.4 inhabitants per square mile (321.9/km2). There were 256,930 housing units at an average density of 375.9 per square mile (145.1/km2). By the 2020 United States census, its population grew to 681,054.[75]

Of Oklahoma City's 579,999 people in 2010, 44,541 resided in Canadian County, 63,723 lived in Cleveland County, 471,671 resided in Oklahoma County, and 64 resided in Pottawatomie County.[76]

In 2010, there were 230,233 households, 29.4% of which had children under 18 living with them, 43.4% were married couples living together, 13.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.4% were non-families. One person households account for 30.5% of all households, and 8.7% of all households had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.47 and the average family size was 3.11.[77]

According to the American Community Survey 1-year estimates in 2022, the median income for a household in the city was $63,713, and the median income for a family was $80,833. Married-couple families $99,839, and nonfamily households $40,521.[78] The per capita income for the city was $35,902.[79] 15.5% of the population and 11.2% of families were below the poverty line. Of the total population, 20.1% of those under 18 and 10.6% of those 65 and older lived below the poverty line.[80]

In the 2000 census, Oklahoma City's age composition was 25.5% under the age of 18, 10.7% from 18 to 24, 30.8% from 25 to 44, 21.5% from 45 to 64, and 11.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females, there were 95.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 92.7 males.

Oklahoma City has experienced significant population increases since the late 1990s. It is the first city in the state to record a population greater than 600,000 residents and the first city in the Great Plains region to record a population greater than 600,000 residents. It is the largest municipal population of the Great Plains region (Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota).[ambiguous]

In the 2020 United States census, there were 268,035 households in the city, out of which 81,374 households (30.4%) were individuals, 113,161 (42.2%) were opposite-sex married couples, 17,699 (6.6%) were unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 2,930 (1.1%) were same-sex married couples or partnerships.[81]

⬤ Black

⬤ Asian

⬤ Hispanic

⬤ Multiracial

⬤ Native American/Other

| Historical racial composition | 2020 [75] | 2010[82] | 1990[23] | 1970[23] | 1940[23] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 49.5% | 56.7% | 72.9% | 82.2% | 90.4% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 21.3% | 17.2% | 5.0% | 2.0% | n/a |

| Black or African American | 13.8% | 14.8% | 16.0% | 13.7% | 9.5% |

| Mixed | 7.6% | 4.0% | 0.4% | – | – |

| Asian | 4.6% | 4.0% | 2.4% | 0.2% | – |

| Native American | 3.4% | 3.1% | 4.2% | 2.0% | 0.1% |

According to the 2020 census, the racial composition of Oklahoma City was as follows:[83] White or European American 49.5%, Hispanic or Latino 21.3%, Black or African American 13.8%, Asian 4.6%, Native American 2.8%, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander 0.2%, other race 0.4%, and two or more races (non-Hispanic) 7.6%. Its population has diversified since the 1940s census, where 90.4% was non-Hispanic white.[23] An analysis in 2017 found Oklahoma City to be the 8th least racially segregated significant city in the United States.[84] Of the 20 largest US cities, Oklahoma City has the second-highest percentage of the population reporting two or more races on the Census, 7.6%, second to 8.9% in New York City.

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[85] | Pop 2010[86] | Pop 2020[87] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 327,225 | 328,582 | 337,063 | 64.65% | 56.65% | 49.49% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 76,994 | 85,744 | 93,767 | 15.21% | 14.78% | 13.77% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 16,406 | 18,208 | 18,757 | 3.24% | 3.14% | 2.75% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 17,410 | 23,051 | 31,163 | 3.44% | 3.97% | 4.58% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 278 | 464 | 971 | 0.05% | 0.08% | 0.14% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 452 | 700 | 2,700 | 0.09% | 0.12% | 0.40% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 15,999 | 23,212 | 51,872 | 3.16% | 4.00% | 7.62% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 51,368 | 100,038 | 144,761 | 10.15% | 17.25% | 21.26% |

| Total | 506,132 | 579,999 | 681,054 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

Oklahoma City is the principal city of the eight-county Oklahoma City metropolitan statistical Area in Central Oklahoma and is the state's largest urbanized area. As of 2015, the metro area was the 41st largest in the nation based on population.[88]

The Association of Religion Data Archives in 2020 reported that the Southern Baptist Convention was the city and metropolitan area's most prominent Christian tradition with 213,008 members, Christianity being the area's predominant religion. Non/interdenominational Protestants were the second largest tradition with 195,158 members. The Roman Catholic Church claimed 142,491 adherents throughout the metropolitan region and Pentecostals within the Assemblies of God USA numbered 48,470.[89] The remainder of Christians in the area held to predominantly Evangelical Christian beliefs in numerous evangelical Protestant denominations. Outside of Christendom, there were 4,230 practitioners of Hinduism and 2,078 Mahayana Buddhists. An estimated 8,904 residents practiced Islam during this study.[89]

Law enforcement claims Oklahoma City has traditionally been the territory of the notorious Juárez Cartel, but the Sinaloa Cartel has been reported as trying to establish a foothold in Oklahoma City. There are many rival gangs in Oklahoma City, one whose headquarters has been established in the city, the Southside Locos, traditionally known as Sureños.[90]

Oklahoma City also has its share of violent crimes, particularly in the 1970s. The worst occurred in 1978 when six employees of a Sirloin Stockade restaurant on the city's south side were murdered execution-style in the restaurant's freezer. An intensive investigation followed, and the three individuals involved, who also killed three others in Purcell, Oklahoma, were identified. One, Harold Stafford, died in a motorcycle accident in Tulsa not long after the restaurant murders. Another, Verna Stafford, was sentenced to life without parole after being granted a new trial after she had been sentenced to death. Roger Dale Stafford, considered the mastermind of the murder spree, was executed by lethal injection at the Oklahoma State Penitentiary in 1995.[91]

The Oklahoma City Police Department has a uniformed force of 1,169 officers and 300+ civilian employees. The department has a central police station and five substations covering 2,500 police reporting districts that average 1/4 square mile in size.

On April 19, 1995, the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building was destroyed by a fertilizer bomb manufactured and detonated by Timothy McVeigh. The blast and catastrophic collapse killed 168 people and injured over 680. The blast shock-wave destroyed or damaged 324 buildings within a 340-meter radius, destroyed or burned 86 cars, and shattered glass in 258 nearby buildings, causing at least an estimated $652 million of damage. McVeigh was convicted and subsequently executed by lethal injection on June 11, 2001.

The economy of Oklahoma City, once just a regional power center of government and energy exploration, has since diversified to include the sectors of information technology, services, health services, and administration. The city is headquarters to two Fortune 500 companies: Expand Energy and Devon Energy,[92] as well as being home to Love's Travel Stops & Country Stores, which is ranked thirteenth on Forbes' list of private companies.[93]

As of March 2024, the top 20 employers in the city were:[94]

| # | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | State of Oklahoma (State Capital) | 37,600 |

| 2 | Tinker Air Force Base | 26,000 |

| 3 | Oklahoma State University-Stillwater | 13,940 |

| 4 | University of Oklahoma-Norman | 11,530 |

| 5 | Integris Health | 11,000 |

| 6 | Amazon | 8,000 |

| 7 | Hobby Lobby Stores (HQ) | 6,500 |

| 8 | Mercy Health Center (HQ) | 6,500 |

| 9 | SSM Health Care (Regional HQ) | 5,600 |

| 10 | FAA Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center | 5,150 |

| 11 | University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center | 5000 |

| 12 | City of Oklahoma City | 4,500 |

| 13 | OU Medical Center | 4,360 |

| 14 | Paycom (HQ) | 4,200 |

| 15 | The Boeing Company | 3,740 |

| 16 | Midfirst Bank (HQ) | 3,100 |

| 17 | Norman Regional Hospital | 2,740 |

| 18 | AT&T | 2,700 |

| 19 | OGE Energy Corp (HQ) | 2,240 |

| 20 | Dell | 2,100 |

Other major corporations with a significant presence (over 1,000 employees) in the city of Oklahoma City include the United Parcel Service, Farmers Insurance Group, Southwest Beverages Coca-Cola Bottling Company, Deaconess Hospital, Johnson Controls, MidFirst Bank, Rose State College, and Continental Resources.[95][96]

While not in the city limits, other large employers within the Oklahoma City MSA include United States Air Force – Tinker AFB (27,000); University of Oklahoma (11,900); University of Central Oklahoma (2,900); and Norman Regional Hospital (2,800).[95]

According to the Oklahoma City Chamber of Commerce, the metropolitan area's economic output grew by 33% between 2001 and 2005 due chiefly to economic diversification. Its gross metropolitan product (GMP) was $43.1 billion in 2005[97] and grew to $61.1 billion in 2009.[98] By 2016 the GMP had grown to $73.8 billion.[99]

In 2008, Forbes magazine reported that the city had falling unemployment, one of the strongest housing markets in the country and solid growth in energy, agriculture, and manufacturing.[100] However, during the early 1980s, Oklahoma City had one of the worst job and housing markets due to the bankruptcy of Penn Square Bank in 1982 and then the post-1985 crash in oil prices (oil bust).[citation needed]

Approximately 23.2 million visitors contributed $4.3 billion to Oklahoma City's economy. These visitors directly spent $2.6 billion, sustained nearly 34,000 jobs, and generated $343 million in state and local taxes.[101]

Business and entertainment districts (and, to a lesser extent, local neighborhoods) tend to maintain their boundaries and character by applying zoning regulations and business improvement districts (districts where property owners agree to a property tax surcharge to support additional services for the community).[102] Through zoning regulations, historic districts, and other special zoning districts, including overlay districts, are well established.[103] Oklahoma City has three business improvement districts, including one encompassing the central business district.

|

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2018)

|

The Donald W. Reynolds Visual Arts Center is the new downtown home for the Oklahoma City Museum of Art. The museum features visiting exhibits, original selections from its collection, a theater showing various foreign, independent, and classic films each week, and a restaurant. OKCMOA is also home to the most comprehensive collection of Chihuly glass in the world, including the 55-foot Eleanor Blake Kirkpatrick Memorial Tower in the Museum's atrium.[104] The art deco Civic Center Music Hall, which was renovated most recently in 2023,[105] has performances from the Oklahoma City Ballet, the Oklahoma City Opera, the Oklahoma City Philharmonic, and also various concerts and traveling Broadway shows.

Other theaters include the Lyric Theatre, Jewel Box Theatre, Kirkpatrick Auditorium, the Poteet Theatre, the Oklahoma City Community College Bruce Owen Theater, and the 488-seat Petree Recital Hall at the Oklahoma City University campus. The university opened the Wanda L Bass School of Music and Auditorium in April 2006.

There are several concert venues across the city hosting major and regional musical artists from across the world. This includes The Criterion, a 3,000 capacity multi-level venue completed in 2016 in Bricktown.[106] The Tower Theater, hosting both concerts and raves, built in 1937 located on 23rd Street right off historic Route 66. The Jones Assembly, a 1,600 capacity venue located in downtown within the city's historic Film Row district.

The Oklahoma Contemporary Arts Center (formerly City Arts Center) moved downtown in 2020, near Campbell Art Park at 11th and Broadway, after being at the Oklahoma State Fair fairgrounds since 1989. It features exhibitions, performances, classes, workshops, camps, and weekly programs.

The Science Museum Oklahoma (formerly Kirkpatrick Science and Air Space Museum at Omniplex) houses exhibits on science and aviation and an IMAX theater. The museum formerly housed the International Photography Hall of Fame (IPHF), which displays photographs and artifacts from an extensive collection of cameras and other artifacts preserving the history of photography. IPHF honors those who have contributed significantly to the art or science of photography and relocated to St. Louis, Missouri in 2013.

The Museum of Osteology displays over 450 real skeletons and houses over 7,000.[107] Focusing on the form and function of the skeletal system, this 7,000 sq ft (650 m2) museum displays hundreds of skulls and skeletons from all corners of the world. Exhibits include adaptation, locomotion, classification, and diversity of the vertebrate kingdom. The Museum of Osteology is the only one of its kind in America.

The National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum has galleries of western art[108] and is home to the Hall of Great Western Performers.[109]

In September 2021, the First Americans Museum opened to the public, focusing on the histories and cultures of the numerous tribal nations and many Indigenous peoples in the state of Oklahoma.[110]

The Oklahoma City National Memorial in the northern part of Oklahoma City's downtown was created as the inscription on its eastern gate of the Memorial reads, "to honor the victims, survivors, rescuers, and all who were changed forever on April 19, 1995"; the memorial was built on the land formerly occupied by the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building complex before its 1995 bombing. The outdoor Symbolic Memorial can be visited 24 hours a day for free, and the adjacent Memorial Museum, in the former Journal Record building damaged by the bombing, can be entered for a small fee. The site is also home to the National Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism, a non-partisan, nonprofit think tank devoted to preventing terrorism.

The American Banjo Museum in the Bricktown Entertainment district is dedicated to preserving and promoting the music and heritage of the banjo.[111] Its collection tells the evolution of the banjo from its roots in American slavery, to bluegrass, to folk, and to world music.

The Oklahoma History Center is the state's history museum. Across the street from the governor's mansion at 800 Nazih Zuhdi Drive in northeast Oklahoma City, the museum opened in 2005 and is operated by the Oklahoma Historical Society. It preserves Oklahoma's history from the prehistoric to the present day.

The Oklahoma State Firefighters Museum contains early colonial firefighting tools, the first fire station in Oklahoma,[112] and modern fire trucks.[113]

The historic 23rd Street Armory in Oklahoma City is set to be transformed into a $23 million entertainment venue by Fischer Companies and TempleLive, featuring a 4,500-capacity theater, a 500-capacity venue for local artists, dining options, and a microbrewery, with construction beginning in spring 2024 and anticipated completion in 2026.[114]

Florence's Restaurant in 2022 was named one of America's Classics by the James Beard Foundation.[115][116] It was the first James Beard award for an Oklahoma entity.[115] The Oklahoman called Florence's "The Grand Dame of all local restaurants".[117] Andrew Black, chef/owner of Grey Sweater, won the 2023 James Beard Award for Best Chef Southwest.[118]

The Food Network show Diners, Drive-Ins, and Dives has been to several restaurants in the Oklahoma City metropolitan area. Some of these include Cattlemen's Steakhouse, Chick N Beer, Clanton's Cafe, The Diner, Eischen's Bar, Florence's Restaurant, and Guyutes, among several others.[119]

Oklahoma City is home to several professional sports teams, including the Oklahoma City Thunder of the National Basketball Association. The Thunder is the city's second "permanent" major professional sports franchise after the now-defunct AFL Oklahoma Wranglers. It is the third major-league team to call the city home when considering the temporary hosting of the New Orleans/Oklahoma City Hornets for the 2005–06 and 2006–07 NBA seasons. However, the Thunder was formerly the Sonics before the movement of the Sonics to OKC in 2008.

Other professional sports clubs in Oklahoma City include the Oklahoma City Comets, the Triple-A affiliate of the Los Angeles Dodgers, the Oklahoma City Energy FC of the United Soccer League, and the Crusaders of Oklahoma Rugby Football Club of USA Rugby. The Oklahoma City Blazers, a name used for decades of the city's hockey team in the Central Hockey League, has been used for a junior team in the Western States Hockey League since 2014.

The Paycom Center in downtown is the main multipurpose arena in the city, which hosts concerts, NHL exhibition games, and many of the city's pro sports teams. In 2008, the Oklahoma City Thunder became the primary tenant. Nearby in Bricktown, the Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark is the home to the city's baseball team, the Comets. "The Brick", as it is locally known, is considered one of the finest minor league parks in the nation.[120]

Oklahoma City hosts the World Cup of Softball and the annual NCAA Women's College World Series. The city has held 2005 NCAA Men's Basketball First and Second round and hosted the Big 12 Men's and women's basketball tournaments in 2007 and 2009. The major universities in the area – University of Oklahoma, Oklahoma City University, and Oklahoma State University – often schedule major basketball games and other sporting events at Paycom Center and Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark. However, most home games are played at their campus stadiums.

Other major sporting events include Thoroughbred and Quarter Horse racing circuits at Remington Park and numerous horse shows and equine events that take place at the state fairgrounds each year. There are multiple golf courses and country clubs spread around the city.

The state of Oklahoma hosts a highly competitive high school football culture, with many teams in the Oklahoma City metropolitan area. The Oklahoma Secondary School Activities Association organizes high school football into eight distinct classes based on school enrollment size. Beginning with the largest, the classes are 6A, 5A, 4A, 3A, 2A, A, B, and C. Class 6A is broken into two divisions. Oklahoma City schools in include: Westmoore, Putnam City North, Putnam City, Putnam City West, Southeast, Capitol Hill, U.S. Grant, and Northwest Classen.[121]

The Oklahoma City Thunder of the National Basketball Association (NBA) has called Oklahoma City home since the 2008–09 season, when owner Clay Bennett relocated the franchise from Seattle, Washington. The Thunder plays home games in downtown Oklahoma City at the Paycom Center. The Thunder is known by several nicknames, including "OKC Thunder" and simply "OKC", and its mascot is Rumble the Bison.

After arriving in Oklahoma City for the 2008–09 season, the Oklahoma City Thunder secured a berth (8th) in the 2010 NBA Playoffs the following year after boasting its first 50-win season, winning two games in the first round against the Los Angeles Lakers. In 2012, Oklahoma City made it to the NBA Finals but lost to the Miami Heat in five games. In 2013, the Thunder reached the Western Conference semi-finals without All-Star guard Russell Westbrook, who was injured in their first-round series against the Houston Rockets, only to lose to the Memphis Grizzlies. In 2014, Oklahoma City reached the NBA's Western Conference Finals again but eventually lost to the San Antonio Spurs in six games.

Sports analysts have regarded the Oklahoma City Thunder as one of the elite franchises of the NBA's Western Conference and a media darling of the league's future. Oklahoma City earned Northwest Division titles every year from 2011 to 2014 and again in 2016 and has consistently improved its win record to 59 wins in 2014. The Thunder is led by third-year head coach Mark Daigneault and is anchored by All-Star point guard Shai Gilgeous-Alexander; acquired from the Los Angeles Clippers in a trade in the summer of 2019. They returned to the NBA Finals in 2025 and defeated the Indiana Pacers in seven games to win their first NBA championship since moving to Oklahoma City.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the NBA's New Orleans Hornets temporarily relocated to the Ford Center, playing the majority of its home games there during the 2005–06 and 2006–07 seasons. The team became the first NBA franchise to play regular-season games in Oklahoma.[122] The team was known as the New Orleans/Oklahoma City Hornets while playing in Oklahoma City. The team returned to New Orleans full-time for the 2007–08 season. The Hornets played their final home game in Oklahoma City during the exhibition season on October 9, 2007, against the Houston Rockets.

| Sports Franchise | League | Sport | Founded | Stadium (capacity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oklahoma City Thunder | NBA | Basketball | 2008 | Paycom Center (18,203) |

| Oklahoma City Comets | MiLB | Baseball | 1998 | Chickasaw Bricktown Ballpark (13,066) |

| Oklahoma City Blue | NBA G League | Basketball | 2018 | Paycom Center (18,203) |

| Oklahoma City Energy | USL Championship (Division 2) | Soccer | 2018 | Taft Stadium (7,500) |

| Oklahoma City Football Club | Women's Premier Soccer League | Soccer | 2022 | Brian Harvey Field (1,500) |

| Oklahoma City Spark | Women's Professional Fastpitch | Softball | 2023 | USA Softball Hall of Fame Stadium (13,500) |

Venues in Oklahoma City will host two events during the 2028 Summer Olympics, which will primarily be held in Los Angeles. The LA Olympic Organizing Committee opted to have canoe slalom and softball in Oklahoma City, given the lack of acceptable venues for those sports in Los Angeles. Riversport OKC will host the canoe slalom competition, while Devon Park will host the softball competition. Oklahoma City is located approximately 1,300 miles away from Los Angeles.[123]

Oklahoma City has more than 170 parks[124] that cover 6,256 acres,[125] and 100 miles of trails.

One of the more prominent landmarks of downtown Oklahoma City is the Crystal Bridge tropical conservatory at the Myriad Botanical Gardens, a large downtown urban park. Designed by I. M. Pei, the park also includes the Water Stage amphitheater, a bandshell, and lawn, a sunken pond complete with koi, an interactive children's garden complete with a carousel and water sculpture, various trails and interactive exhibits that rotate throughout the year including the ice skating in the Christmas winter season. In 2007, following a renovation of the stage, Oklahoma Shakespeare In The Park relocated to the Myriad Gardens. Bicentennial Park, also downtown located near the Oklahoma City Civic Center campus, is home to the annual Festival of the Arts in April.

The Scissortail Park is just south of the Myriad Gardens, a large interactive park that opened in 2021. This park contains a large lake with paddleboats, a dog park, a concert stage with a great lawn, a promenade including the Skydance Bridge, a children's interactive splash park and playground, and numerous athletic facilities. Farmers Market is a common attraction at Scissortail Park during the season, and there are multiple film showings, food trucks, concerts, festivals, and civic gatherings.

Returning to the city's first parks masterplan, Oklahoma City has at least one major park in each quadrant outside downtown. Will Rogers Park, the Grand Boulevard loop once connected Lincoln Park, Trosper Park, and Woodson Park, some sections of which no longer exist. Martin Park Nature Center is a natural habitat in far northwest Oklahoma City. Will Rogers Park is home to the Lycan Conservatory, the Rose Garden, and the Butterfly Garden, all built in the WPA era. In April 2005, the Oklahoma City Skate Park at Wiley Post Park was renamed the Mat Hoffman Action Sports Park to recognize Mat Hoffman, an Oklahoma City area resident and businessman who was instrumental in the design of the skate park and is a 10-time BMX World Vert champion.[126]

Walking trails line the Bricktown Canal and the Oklahoma River in downtown. The city's bike trail system follows around Lake Hefner and Lake Overholser in the northwest and west quadrants of the city. The majority of the east shore area of Lake Hefner is taken up by parks and bike trails, including a new leashless dog park and the postwar-era Stars and Stripes Park, and eateries near the lighthouse. Lake Stanley Draper, in southeast Oklahoma City, is the city's largest and most remote lake, offering a genuine rural yet still urban experience.

The Oklahoma City Zoo and Botanical Garden is home to numerous natural habitats, WPA era architecture and landscaping, and major touring concerts during the summer at its amphitheater. Nearby is a combination racetrack and casino, Remington Park, which hosts both Quarter Horse (March – June) and Thoroughbred (August—December) seasons.

Oklahoma City is also home to the American Banjo Museum, which houses a large collection of highly decorated banjos from the early 20th century and exhibits the banjo's history and its place in American history. Concerts and lectures are also held there.

The City of Oklahoma City has operated under a council-manager form of city government since 1927.[127] David Holt assumed the office of Mayor on April 10, 2018, after being elected two months earlier.[128] Eight councilpersons represent each of the eight wards of Oklahoma City. The City Council appointed current City Manager Craig Freeman on November 20, 2018. Freeman took office on January 2, 2018, succeeding James D. Couch, who had served in the role since 2000. Before becoming City Manager, Craig Freeman served as Finance Director for the city.[129]

Similar to many American cities, Oklahoma City is politically conservative in its suburbs and liberal in the central city. In the United States House of Representatives, it is represented by Republicans Stephanie Bice, Tom Cole, and Frank Lucas of the 5th, 4th, and 3rd districts, respectively. The city has called on residents to vote for sales tax-based projects to revitalize parts of the city. The Bricktown district is the best example of such an initiative. In the recent MAPS 3 vote, the city's fraternal police order criticized the project proposals for not doing enough to expand the police presence to keep up with the growing residential population and increased commercial activity. In September 2013, Oklahoma City area attorney David Slane announced he would pursue legal action regarding MAPS3 on claims the multiple projects that made up the plan violate a state constitutional law limiting voter ballot issues to a single subject.[130]

| Oklahoma County Voter Registration and Party Enrollment as of January 15, 2025[131] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of Voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 161,443 | 33.9% | |||

| Republican | 197,346 | 41.4% | |||

| Libertarian | 5,058 | 1.1% | |||

| Unaffiliated | 112,275 | 23.6% | |||

| Total | 476,122 | 100% | |||

| Consulate | Date | Consular District |

| Guatemalan Consulate-General, Oklahoma City[132] | 06.2017 | Oklahoma, Kansas |

| Mexican Consulate, Oklahoma City[133] | 05.2023 | Oklahoma |

| Germany Honorary Consulate, Oklahoma City |

Oklahoma City's sister cities are:[134]

The city is home to several colleges and universities. Oklahoma City University, formerly known as Epworth University, was founded by the United Methodist Church on September 1, 1904, and is known for its performing arts, science, mass communications, business, law, and athletic programs. OCU has its main campus in the north-central section of the city, near the city's Asia District area. OCU Law is in the old Central High School building in the Midtown district near downtown.

The University of Oklahoma has several institutions of higher learning in the city and metropolitan area, with OU Medicine and the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center campuses east of downtown in the Oklahoma Health Center district, and the main campus to the south in the suburb of Norman. OU Medical Center hosts the state's only Level-One trauma center. OU Health Sciences Center is one of the nation's largest independent medical centers, employing over 12,000 people.[135] OU is one of only four major universities in the nation to operate six medical schools.[clarification needed]

The third-largest university in the state, the University of Central Oklahoma, is just north of the city in the suburb of Edmond. Oklahoma Christian University, one of the state's private liberal arts institutions, is just south of the Edmond border, inside the Oklahoma City limits.[136]

Oklahoma City Community College in south Oklahoma City is the second-largest community college in the state. Rose State College is east of Oklahoma City in suburban Midwest City. Oklahoma State University–Oklahoma City is in the "Furniture District" on the Westside. Northeast of the city is Langston University, the state's historically black college (HBCU). Langston also has an urban campus in the eastside section of the city. Southern Nazarene University, which was founded by the Church of the Nazarene, is a university in suburban Bethany, which is surrounded by the Oklahoma City city limits.

Although technically not a university, the FAA's Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center has many aspects of an institution of higher learning. Its FAA Academy is accredited by the Higher Learning Commission. Its Civil Aerospace Medical Institute (CAMI) has a medical education division responsible for aeromedical education in general, as well as the education of aviation medical examiners in the U.S. and 93 other countries. In addition, The National Academy of Science offers Research Associateship Programs for fellowship and other grants for CAMI research.

Oklahoma City is home to (as of 2009) the state's largest school district, Oklahoma City Public Schools,[137] which covers the most significant portion of the city.[138] The district's Classen School of Advanced Studies and Harding Charter Preparatory High School rank high among public schools nationally according to a formula that looks at the number of Advanced Placement, International Baccalaureate or Cambridge tests taken by the school's students divided by the number of graduating seniors.[139] In addition, OKCPS's Belle Isle Enterprise Middle School was named the top middle school in the state according to the Academic Performance Index and recently received the Blue Ribbon School Award, in 2004 and again in 2011.[140]

Due to Oklahoma City's explosive growth, parts of several suburban districts spill into the city. All but one of the school districts in Oklahoma County includes portions of Oklahoma City. The other districts in that county covering OKC include: Choctaw/Nicoma Park, Crooked Oak, Crutcho, Deer Creek, Edmond, Harrah, Jones, Luther, McLoud, Mid-Del, Millwood, Moore, Mustang, Oakdale, Piedmont, Putnam City, and Western Heights.[138] School districts in Cleveland County covering portions of Oklahoma City include: Little Axe, McLoud, Mid-Del, Moore, and Robin Hill.[141] Within Canadian County, Banner, Mustang, Piedmont, Union City, and Yukon school districts include parts of OKC.[142]

There are also charter schools. KIPP Reach College Preparatory School in Oklahoma City received the 2012 National Blue Ribbon, and its school leader, Tracy McDaniel Sr., was awarded the Terrel H. Bell Award for Outstanding Leadership.

The city also boasts several private and parochial schools. Casady School and Heritage Hall School are both examples of a private college preparatory school with rigorous academics that range among the top in Oklahoma. Providence Hall is a Protestant school. Two prominent schools of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City include Bishop McGuinness High School and Mount Saint Mary High School. Other private schools include the Advanced Science and Technology Education Center and Crossings Christian School.

The Oklahoma School of Science and Mathematics, a school for some of the state's most gifted math and science pupils, is also in Oklahoma City.

Oklahoma City has several public career and technology education schools associated with the Oklahoma Department of Career and Technology Education, the largest of which are Metro Technology Center and Francis Tuttle Technology Center.

Private career and technology education schools in Oklahoma City include Oklahoma Technology Institute, Platt College, Vatterott College, and Heritage College. The Dale Rogers Training Center is a nonprofit vocational training center for individuals with disabilities.