Skilled trade

"Carpenters" and "Carpenter" redirect here. For the American pop duo, see The Carpenters. For other uses, see Carpenter (disambiguation).

Carpentry

|

|

Occupation type

|

Professional |

|

Activity sectors

|

Construction |

|

Education required

|

No |

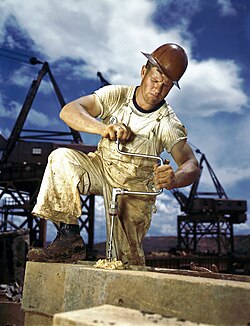

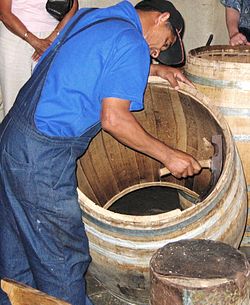

Carpentry includes such specialties as barrelmaker, cabinetmaker, framer, luthier, and ship's carpenter

Carpentry includes such specialties as barrelmaker, cabinetmaker, framer, luthier, and ship's carpenter

Exhibit of traditional European carpenter's tools in Italy

Exhibit of traditional European carpenter's tools in Italy

Carpenters in an Indian village working with hand tools

Carpenters in an Indian village working with hand tools

Carpentry is a skilled trade and a craft in which the primary work performed is the cutting, shaping and installation of building materials during the construction of buildings, ships, timber bridges, concrete formwork, etc. Carpenters traditionally worked with natural wood and did rougher work such as framing, but today many other materials are also used[1] and sometimes the finer trades of cabinetmaking and furniture building are considered carpentry. In the United States, 98.5% of carpenters are male, and it was the fourth most male-dominated occupation in the country in 1999. In 2006 in the United States, there were about 1.5 million carpentry positions. Carpenters are usually the first tradesmen on a job and the last to leave.[2] Carpenters normally framed post-and-beam buildings until the end of the 19th century; now this old-fashioned carpentry is called timber framing. Carpenters learn this trade by being employed through an apprenticeship training—normally four years—and qualify by successfully completing that country's competence test in places such as the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Switzerland, Australia and South Africa.[3] It is also common that the skill can be learned by gaining work experience other than a formal training program, which may be the case in many places.

Carpentry covers various services, such as furniture design and construction, door and window installation or repair, flooring installation, trim and molding installation, custom woodworking, stair construction, structural framing, wood structure and furniture repair, and restoration.

Etymology

[edit]

The word "carpenter" is the English rendering of the Old French word carpentier (later, charpentier) which is derived from the Latin carpentarius [artifex], "(maker) of a carriage."[4] The Middle English and Scots word (in the sense of "builder") was wright (from the Old English wryhta, cognate with work), which could be used in compound forms such as wheelwright or boatwright.[5]

In the United Kingdom

[edit]

In the UK, carpentry is used to describe the skill involved in first fixing of timber items such as construction of roofs, floors and timber framed buildings, i.e. those areas of construction that are normally hidden in a finished building. An easy way to envisage this is that first fix work is all that is done before plastering takes place. The second fix is done after plastering takes place. Second fix work, the installation of items such as skirting boards, architraves, doors, and windows are generally regarded as carpentry, however, the off-site manufacture and pre-finishing of the items is regarded as joinery.[6][7] Carpentry is also used to construct the formwork into which concrete is poured during the building of structures such as roads and highway overpasses. In the UK, the skill of making timber formwork for poured or in situ concrete is referred to as shuttering.

In the United States

[edit]

Carpentry in the United States is historically defined similarly to the United Kingdom as the "heavier and stronger"[8] work distinguished from a joiner "...who does lighter and more ornamental work than that of a carpenter..." although the "...work of a carpenter and joiner are often combined."[9] Joiner is less common than the terms finish carpenter or cabinetmaker. The terms housewright and barnwright were used historically and are now occasionally used by carpenters who work using traditional methods and materials. Someone who builds custom concrete formwork is a form carpenter.

History

[edit]

Log church building in Russia reached considerable heights such as this 17th century example

Log church building in Russia reached considerable heights such as this 17th century example

Along with stone, wood is among the oldest building materials. The ability to shape it into tools, shelter, and weapons improved with technological advances from the Stone Age to the Bronze Age to the Iron Age. Some of the oldest archaeological evidence of carpentry are water well casings. These include an oak and hazel structure dating from 5256 BC, found in Ostrov, Czech Republic,[10] and one built using split oak timbers with mortise and tenon and notched corners excavated in eastern Germany, dating from about 7,000 years ago in the early Neolithic period.[11]

Relatively little history of carpentry was preserved before written language. Knowledge and skills were simply passed down over the generations. Even the advent of cave painting and writing recorded little. The oldest surviving complete architectural text is Vitruvius' ten books collectively titled De architectura, which discuss some carpentry.[citation needed] It was only with the invention of the printing press in the 15th century that this began to change, albeit slowly, with builders finally beginning to regularly publish guides and pattern books in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Some of the oldest surviving wooden buildings in the world are temples in China such as the Nanchan Temple built in 782, Greensted Church in England, parts of which are from the 11th century, and the stave churches in Norway from the 12th and 13th centuries.

Europe

[edit]

By the 16th century, sawmills were coming into use in Europe. The founding of America was partly based on a desire to extract resources from the new continent including wood for use in ships and buildings in Europe. In the 18th century part of the Industrial Revolution was the invention of the steam engine and cut nails.[12] These technologies combined with the invention of the circular saw led to the development of balloon framing which was the beginning of the decline of traditional timber framing.

Axonometric diagram of balloon framing

Axonometric diagram of balloon framing

The 19th century saw the development of electrical engineering and distribution which allowed the development of hand-held power tools, wire nails, and machines to mass-produce screws. In the 20th century, portland cement came into common use and concrete foundations allowed carpenters to do away with heavy timber sills. Also, drywall (plasterboard) came into common use replacing lime plaster on wooden lath. Plywood, engineered lumber, and chemically treated lumber also came into use.[13]

For types of carpentry used in America see American historic carpentry.

Training

[edit]

Carpentry requires training which involves both acquiring knowledge and physical practice. In formal training a carpenter begins as an apprentice, then becomes a journeyman, and with enough experience and competency can eventually attain the status of a master carpenter. Today pre-apprenticeship training may be gained through non-union vocational programs such as high school shop classes and community colleges.

Informally a laborer may simply work alongside carpenters for years learning skills by observation and peripheral assistance. While such an individual may obtain journeyperson status by paying the union entry fee and obtaining a journeyperson's card (which provides the right to work on a union carpentry crew) the carpenter foreperson will, by necessity, dismiss any worker who presents the card but does not demonstrate the expected skill level.

Carpenters may work for an employer or be self-employed. No matter what kind of training a carpenter has had, some U.S. states require contractors to be licensed which requires passing a written test and having minimum levels of insurance.

Schools and programs

[edit]

Formal training in the carpentry trade is available in seminars, certificate programs, high-school programs, online classes, in the new construction, restoration, and preservation carpentry fields.[14] Sometimes these programs are called pre-apprenticeship training.

In the modern British construction industry, carpenters are trained through apprenticeship schemes where general certificates of secondary education (GCSE) in Mathematics, English, and Technology help but are not essential. However, this is deemed the preferred route, as young people can earn and gain field experience whilst training towards a nationally recognized qualification.

There are two main divisions of training: construction-carpentry and cabinetmaking. During pre-apprenticeship, trainees in each of these divisions spend 30 hours a week for 12 weeks in classrooms and indoor workshops learning mathematics, trade terminology, and skill in the use of hand and power tools. Construction-carpentry trainees also participate in calisthenics to prepare for the physical aspect of the work.

Upon completion of pre-apprenticeship, trainees who have passed the graded curriculum (taught by highly experienced journeyperson carpenters) are assigned to a local union and to union carpentry crews at work on construction sites or in cabinet shops as First Year Apprentices. Over the next four years, as they progress in status to Second Year, Third Year, and Fourth Year Apprentice, apprentices periodically return to the training facility every three months for a week of more detailed training in specific aspects of the trade.

In the United States, fewer than 5% of carpenters identify as female. A number of schools in the U.S. appeal to non-traditional tradespeople by offering carpentry classes for and taught by women, including Hammerstone: Carpentry for Women in Ithaca, NY, Yestermorrow in Waitsfield, VT and Oregon Tradeswomen in Portland, OR.

Apprenticeships and journeyperson

[edit]

Tradesmen in countries such as Germany and Australia are required to fulfill formal apprenticeships (usually three to four years) to work as professional carpenters. Upon graduation from the apprenticeship, they are known as journeyperson carpenters.

Up through the 19th and even the early 20th century, the journeyperson traveled to another region of the country to learn the building styles and techniques of that area before (usually) returning home. In modern times, journeypeople are not required to travel, and the term now refers to a level of proficiency and skill. Union carpenters in the United States, that is, members of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America, are required to pass a skills test to be granted official journeyperson status, but uncertified professional carpenters may also be known as journeypersons based on their skill level, years of experience, or simply because they support themselves in the trade and not due to any certification or formal woodworking education.

Professional status as a journeyperson carpenter in the United States may be obtained in a number of ways. Formal training is acquired in a four-year apprenticeship program administered by the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America, in which journeyperson status is obtained after successful completion of twelve weeks of pre-apprenticeship training, followed by four years of on-the-job field training working alongside journeyperson carpenters. The Timber Framers Guild also has a formal apprenticeship program for traditional timber framing. Training is also available in groups like the Kim Bồng woodworking village in Vietnam where apprentices live and work to learn woodworking and carpentry skills.

In Canada, each province sets its own standards for apprenticeship. The average length of time is four years and includes a minimum number of hours of both on-the-job training and technical instruction at a college or other institution. Depending on the number of hours of instruction an apprentice receives, they can earn a Certificate of Proficiency, making them a journeyperson, or a Certificate of Qualification, which allows them to practice a more limited amount of carpentry. Canadian carpenters also have the option of acquiring an additional Interprovincial Red Seal that allows them to practice anywhere in Canada. The Red Seal requires the completion of an apprenticeship and an additional examination.

Master carpenter

[edit]

After working as a journeyperson for a while, a carpenter may go on to study or test as a master carpenter. In some countries, such as Germany, Iceland and Japan, this is an arduous and expensive process, requiring extensive knowledge (including economic and legal knowledge) and skill to achieve master certification; these countries generally require master status for anyone employing and teaching apprentices in the craft. In others, like the United States, 'master carpenter' can be a loosely used term to describe any skilled carpenter.

Fully trained carpenters and joiners will often move into related trades such as shop fitting, scaffolding, bench joinery, maintenance and system installation.

Materials

[edit]

The Centre Pompidou-Metz museum under construction in Metz, France. The building possesses one of the most complex examples of carpentry built to date and is composed of 16 kilometers of glued laminated timber for a surface area of 8,000 m2.

The Centre Pompidou-Metz museum under construction in Metz, France. The building possesses one of the most complex examples of carpentry built to date and is composed of 16 kilometers of glued laminated timber for a surface area of 8,000 m2.

Carpenters traditionally worked with natural wood which has been prepared by splitting (riving), hewing, or sawing with a pit saw or sawmill called lumber (American English) or timber (British English). Today natural and engineered lumber and many other building materials carpenters may use are typically prepared by others and delivered to the job site. In 2013 the carpenters union in America used the term carpenter for a catch-all position. Tasks performed by union carpenters include installing "...flooring, windows, doors, interior trim, cabinetry, solid surface, roofing, framing, siding, flooring, insulation, ...acoustical ceilings, computer-access flooring, metal framing, wall partitions, office furniture systems, and both custom or factory-produced materials, ...trim and molding,... ceiling treatments, ... exposed columns and beams, displays, mantels, staircases...metal studs, metal lath, and drywall..."[15]

Health and safety

[edit]

United States

[edit]

Carpentry is often hazardous work. Types of woodworking and carpentry hazards include: machine hazards, flying materials, tool projection, fire and explosion, electrocution, noise, vibration, dust, and chemicals. In the United States the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) tries to prevent illness, injury, and fire through regulations. However, self-employed workers are not covered by the OSHA act.[16] OSHA claims that "Since 1970, workplace fatalities have been reduced by more than 65 percent and occupational injury and illness rates have declined by 67 percent. At the same time, U.S. employment has almost doubled."[17] The leading cause of overall fatalities, called the "fatal four," are falls, followed by struck by object, electrocution, and caught-in/between. In general construction "employers must provide working conditions that are free of known dangers. Keep floors in work areas in a clean and, so far as possible, dry condition. Select and provide required personal protective equipment at no cost to workers. Train workers about job hazards in a language that they can understand."[18] Examples of how to prevent falls includes placing railings and toe-boards at any floor opening which cannot be well covered and elevated platforms and safety harness and lines, safety nets, stair railings, and handrails.

Safety is not just about the workers on the job site. Carpenters' work needs to meet the requirements in the Life Safety Code such as in stair building and building codes to promote long-term quality and safety for the building occupants.

Types of carpentry

[edit]

A team of carpenters assembling a Tarrant hut during World War I

A team of carpenters assembling a Tarrant hut during World War I

- Conservation carpenter works in architectural conservation, known in the U.S. as a "preservation" or "restoration"; a carpenter who works in historic preservation, maintaining structures as they were built or restoring them to that condition.

- Cooper, a barrel maker.

- Formwork carpenter creates the shuttering and falsework used in concrete construction, and reshores as necessary.

- Framer is a carpenter who builds the skeletal structure or wooden framework of buildings, most often in the platform framing method. A framer who specializes in building with timbers and traditional joints rather than studs is known as a timber framer.

- Log builder builds structures of stacked horizontal logs with limited joints.

- Joiner (a traditional name now rare in North America), is one who does cabinetry, furniture making, fine woodworking, model building, instrument making, parquetry, joinery, or other carpentry where exact joints and minimal margins of error are important. Various types of joinery include:

- Cabinetmaker is a carpenter who does fine and detailed work specializing in the making of cabinets made from wood, wardrobes, dressers, storage chests, and other furniture designed for storage.

- Finish carpenter (North America), also trim carpenter, specializes in installing millwork ie; molding and trim, (such as door and window casings, mantels, crown mouldings, baseboards), engineered wood panels, wood flooring and other types of ornamental work such as turned or Carved objects. Finish carpenters pick up where framing ends off, including hanging doors and installing cabinets. Finish Carpenters are often referred to colloquially as "millworkers", but this title actually pertains to the creation of moldings on a mill.

- Furniture maker is a carpenter who makes standalone furniture such as tables, and chairs.

- Luthier is someone who makes or repairs stringed instruments. The word luthier comes from the French word for lute, "luth".

- Set carpenter builds and dismantles temporary scenery and sets in film-making, television, and the theater.

- Shipwright specializes in fabrication maintenance, repair techniques, and carpentry specific to vessels afloat. When assigned to a ship's crew would they would be known as a "Ship's Carpenter". Such a carpenter patrols the vessel's carpenter's walk to examine the hull for leaks.

Other

[edit]

- Japanese carpentry, daiku is the simple term for carpenter, a Miya-daiku (temple carpenter) performs the work of both architect and builder of shrines and temples, and a sukiya-daiku works on teahouse construction and houses. Sashimono-shi build furniture and tateguya do interior finishing work.[19]

- Green carpentry specializes in the use of environmentally friendly,[20] energy-efficient[21] and sustainable[22] sources of building materials for use in construction projects. They also practice building methods that require using less material and material that has the same structural soundness.[23]

- Recycled (reclaimed, repurposed) carpentry is carpentry that uses scrap wood and parts of discarded or broken furniture to build new wood products.

See also

[edit]

- Japanese carpentry – Distinctive woodworking style

- Ship's carpenter – Ship crewman responsible for maintaining wooden structures

- Traditional trades – Category of building trades

- Woodworking – Process of making objects from wood

- Worshipful Company of Carpenters – Livery company of the City of London

References

[edit]

- ^ Roza, Greg. A career as a . New York: Rosen Pub., 2011. 6. Print.

- ^ Vogt, Floyd, and Gaspar J. Lewis. Carpentry. 4th ed. Clifton Park, NY: Thomson Delmar Learning, 2006.xvi Print.

- ^

"Carpenter | Careers in Construction". www.careersinconstruction.ca.

- ^ The American heritage dictionary of the English language Archived June 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine - Etymology of the word "carpenter"

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000.

- ^ "What's the Difference Between a Carpenter and a Joiner?" (30 April 2015). InternationalTimber.com. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ "Joiner vs Carpenter - What's the Difference?".

- ^ "Carpenter." Def. 1. Oxford English Dictionary Second Edition on CD-ROM (v. 4.0) © Oxford University Press 2009

- ^ Whitney, William D., ed. "Carpenter." Def, 1. The Century Dictionary: An Encyclopedic Lexicon of the English Language vol. 1. New York. The Century Co. 1895. 830. Print.

- ^ RybníÄek, Michal; KoÄár, Petr; Muigg, Bernhard; Peška, Jaroslav; SedláÄek, Radko; Tegel, Willy; KoláÅ™, Tomáš (2020). "World's oldest dendrochronologically dated archaeological wood construction". Journal of Archaeological Science. 115: 105082. Bibcode:2020JArSc.115j5082R. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2020.105082. S2CID 213707193.

- ^ Prostak, Sergio (24 December 2012). "German Archaeologists Discover World's Oldest Wooden Wells". sci-news.com.

- ^ Loveday, Amos John. The cut nail industry, 1776–1890: technology, cost accounting, and the upper Ohio Valley. Ann Arbor, Mich.: University Microfilms International, 1979. Print.

- ^ Jester, Thomas C.. Twentieth-century building materials: history and conservation. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1995. Print.

- ^ [1] Archived April 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "United Brotherhood Of Carpenters". carpenters.org. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ^ "Workers' Rights". osha.gov. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ^ "Commonly Used Statistics". osha.gov. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ^ "Safety and Health Topics - Fall Protection". osha.gov. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ^ Lee Butler, "Patronage and the Building Arts in Tokugawa Japan", Early Modern Japan. Fall-Winter 2004 [2]

- ^ "Environmentally Friendly Building Materials". McMullen Carpenters And Joiners. 2009-04-10. Archived from the original on 2013-06-28. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- ^ "A Green Home Begins with ENERGY STAR Blue" (PDF). Energystar. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

- ^ "Green Building Basics". Ciwmb.ca.gov. Archived from the original on 2009-12-10. Retrieved 2012-05-21.

- ^ "Defining Green-Collar Jobs" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

There is no consensus on how to define green-collar jobs. A very broad interpretation of green jobs would include all existing and new jobs that contribute to environmental quality through improved efficiencies, better resource management, and other technologies that successfully address the environmental challenges facing society. Probably the most concise, general definition is "well-paid, career-track jobs that contribute directly to preserving or enhancing environmental quality" (Apollo Alliance 2008, 3). This definition suggests that green-collar jobs directly contribute to improving environmental quality, but would not include low-wage jobs that provide little mobility. Most discussion of green-collar jobs does not refer to positions that require a college degree, but they typically do involve training beyond high school. Many of the positions are similar to skilled, blue-collar jobs, such as electricians, welders, carpenters, etc.

[1]

External links

[edit]

Look up carpentry in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.