The flexibility of telemedicine appointments allowed him to seek treatment without disrupting his day. First off, let's talk about your diet. Learn more about Women's Headache Treatment California here They consider everything from medication and diet to stress management techniques and physical therapy options. Regular physical activity can reduce the frequency and intensity of migraines for many. Learn more about Haven Headache & Migraine Center here. By understanding the genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors that trigger your migraines, we're working towards preventative approaches that minimize your migraine episodes and their severity.

Headaches are pain in any region of the head, often described as ranging from mild to severe. Discussing your symptoms and concerns through a screen can sometimes feel less intimidating, making it easier to communicate openly with your healthcare provider. At Haven Headache & Migraine Center, the focus is on understanding the nuances of your condition through comprehensive online consultations. To get started, simply visit the Haven Headache & Migraine Center's website or give them a call. Headache Management Program

Turning to telehealth, she found a specialist who tailored a treatment plan that drastically reduced her migraine frequency and severity. It's straightforward and ensures your appointment addresses your specific needs right from the start. This shift towards online medical services isn't just a trend but a substantial step forward in making healthcare more accessible and tailored to your needs. So, they're not just treating your migraines; they're looking after you, ensuring the treatment plan fits your lifestyle and preferences.

During this session, you can discuss your symptoms, medical history, and any concerns you have just as you'd during an in-person visit. The specialist will assess your situation, offer recommendations, and can even prescribe medication if necessary. You'll also have the opportunity to ask questions and clarify any concerns. Another success story comes from Mike, a busy professional whose chronic headaches made it difficult to maintain his work schedule.

In essence, Haven Headache & Migraine Center offers a comprehensive, ongoing support system designed to empower you in managing your migraines effectively, ensuring you always feel supported and never alone on your path to relief.

| Entity Name | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Headache | A pain or discomfort in the head or face area, often caused by various conditions. | source |

| Migraine | A neurological condition characterized by intense, debilitating headaches often with nausea. | source |

| Cluster headache | Severe headaches occurring in cyclical patterns or clusters, typically around one eye. | source |

| Tension headache | A common type of headache caused by muscle tension and stress, resulting in a dull pain. | source |

| Long COVID | Prolonged symptoms and health effects following infection with COVID-19. | source |

| Migraine-associated vertigo | Vertigo or dizziness occurring in conjunction with migraine headaches. | source |

| Aura (symptom) | Sensory disturbances such as visual changes preceding a migraine attack. | source |

| Nausea | A sensation of unease and discomfort in the stomach often preceding vomiting. | source |

| Lightheadedness | Feeling faint or dizzy, often due to reduced blood flow to the brain. | source |

| Weakness | Lack of physical strength or energy in muscles or the body. | source |

| Neck pain | Discomfort or pain localized in the neck region, often due to injury or strain. | source |

| Sleep disorder | Conditions affecting the quality, timing, and amount of sleep, impacting health. | source |

| Sinusitis | Inflammation or infection of the sinus cavities causing pain and congestion. | source |

| Orofacial pain | Pain perceived in the face and/or oral cavity, often involving nerves or muscles. | source |

| Trigeminal neuralgia | Chronic pain condition affecting the trigeminal nerve in the face, causing severe facial pain. | source |

| Trigeminal nerve | The fifth cranial nerve responsible for sensation in the face and motor functions like biting. | source |

| Chronic pain | Persistent pain lasting longer than usual recovery time, often beyond 3 months. | source |

| Pain | An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage. | source |

The Greater Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay areas are the nation's second- and fifth-most populous urban regions, with 19 million and 10 million residents respectively. Los Angeles is the state's most populous city and the nation's second-most. California's capital is Sacramento. Part of the Californias region of North America, the state's diverse geography ranges from the Pacific Coast and metropolitan areas in the west to the Sierra Nevada mountains in the east, and from the redwood and Douglas fir forests in the northwest to the Mojave Desert in the southeast. Two-thirds of the nation's earthquake risk lies in California. The Central Valley, a fertile agricultural area, dominates the state's center. The large size of the state results in climates that vary from moist temperate rainforest in the north to arid desert in the interior, as well as snowy alpine in the mountains. Droughts and wildfires are an ongoing issue,[13] while simultaneously, atmospheric rivers are turning increasingly prevalent and leading to intense flooding events—especially in the winter.

Tracking your symptoms, identifying your triggers, and recognizing the early warning signs can help you take control. Neurology Clinic Haven's commitment to ongoing care ensures that you're supported every step of the way towards achieving a better quality of life free from debilitating migraines. You can easily schedule follow-up appointments, monitor your progress, and make adjustments to your treatment plan in real time. Moreover, virtual consultations can be more cost-effective and time-saving. Many services offer consultations during evenings and weekends, ensuring you get the help you need when you need it.

Haven incorporates lifestyle adjustments, dietary recommendations, and stress management techniques into your plan. Changes in weather? You'll discuss your symptoms and concerns in a familiar and secure environment, enhancing the quality of the consultation. Migraine Diagnosis Seeking expert care for headaches and migraines has never been more convenient, thanks to the benefits of online consultations.

If you're a Women's Headache Treatment California resident struggling with the relentless waves of migraine pain, you've likely sought refuge in various treatments with little to no success. Recognizing your unique migraine triggers is a crucial step, but finding the right treatment options at specialized centers like Haven Headache & Migraine Center can significantly improve your quality of life. Building on our commitment to personalized care plans, we also embrace a holistic approach to treating your migraines. This means they not only meet but often exceed, the requirements for privacy and security in healthcare. Pain Management

When your appointment time arrives, you'll log into the platform using your computer or mobile device. Next, you'll schedule a virtual meeting with a Haven migraine specialist. Recognizing early signs of a migraine can help you take action before it fully develops. Here, you'll select an available slot that fits your schedule.

Instead, expert advice will be just a video call away, saving you time and hassle.

With personalized care at your fingertips, relief is closer than you think. This collaborative approach fosters a deeper understanding of your condition, paving the way for personalized treatment plans that align with your lifestyle and preferences. Haven's medical professionals are leaders in their field, equipped with the tools to provide top-notch care digitally. Migraine Headache Clinic We'll work with you to identify potential triggers in your diet, daily routine, and environment that may be contributing to your migraines. Moreover, telehealth's rise has empowered you to take control of your health journey.

This means you're not getting a one-size-fits-all approach but rather a strategy that considers your symptoms, triggers, and daily routines. Then there's Emma, who lives in a remote part of Women's Headache Treatment California with limited access to specialized healthcare. You'll find that our center prioritizes lifestyle adjustments, dietary changes, and stress management techniques as key components of your treatment plan. This step ensures your consultation is tailored to your needs right from the start.

She went from chronic daily headaches to enjoying her hobbies again, pain-free. These gatherings are led by experts and cover a wide range of topics, from managing stress and anxiety associated with migraines to exploring new research and treatment options. They'll guide you through lifestyle changes that can significantly impact your migraine experience. It's important to take notes during your consultation or ask for a summary via email so you can refer back to them.

By choosing Haven, you're putting yourself in the hands of specialists who genuinely care and have the skills to make a difference in your life. Plus, Haven's app tracks your progress and symptoms, offering insights that help fine-tune your treatment over time. You can schedule appointments, consult with specialists, and even receive prescriptions online.

These stories aren't just testimonials; they're proof of the efficacy and convenience of telehealth in treating chronic conditions like migraines. They're also skilled in leveraging telehealth technology, ensuring you have access to their expertise regardless of your location in Women's Headache Treatment California. This isn't a distant dream; it's the near future of migraine management. She's just one of many who've found relief without the stress of commuting to a medical office.

Our goal isn't just to manage your migraines; it's to enhance your overall quality of life.

We believe in empowering you with knowledge, so you'll understand not just the 'how' but the 'why' behind your migraines. Tension Headache Therapy To effectively manage migraines, it's crucial to grasp what they are and how they impact your body. When you're seeking care through their telehealth services, you're not just getting convenience; you're also receiving a commitment to your confidentiality. Migraine Doctors You'll receive a clear explanation of how your information is used and safeguarded, giving you control over your medical data.

First, we'll help you understand your insurance policy's specifics. Through telehealth, he got access to a headache specialist who helped him with ergonomic adjustments and prescribed medication that worked wonders. It's breaking down barriers, making it easier for you to manage your health on your terms.

You'll also appreciate the privacy and comfort online consultations offer. It's particularly beneficial for those living in rural or underserved areas, where specialist care is scarce. So, you're not just getting standard care; you're benefiting from the latest in migraine management, all from the comfort of your home.

Living with chronic headaches can significantly disrupt your daily life, making even simple tasks seem insurmountable. Understanding your journey with headaches and migraines, we provide continuous care and unwavering support throughout your treatment. Moreover, Haven's support goes beyond direct medical interventions.

| Migraine | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Woman during a migraine attack | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Headaches coupled with sensory disturbances such as nausea, sensitivity to light, sound, and smell |

| Usual onset | Around puberty |

| Duration | Recurrent, long term |

| Causes | Environmental and genetic |

| Risk factors | Family history, female sex |

| Differential diagnosis | Subarachnoid hemorrhage, venous thrombosis, idiopathic intracranial hypertension, brain tumor, tension headache, sinusitis, cluster headache |

| Prevention | Propranolol, amitriptyline, topiramate, calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonists (CGRPs) |

| Medication | Ibuprofen, paracetamol (acetaminophen), triptans, ergotamines |

| Prevalence | ~15% |

Migraine ( UK: /ˈmiːɡreɪn/,

US: /ˈmaɪ-/)[1][2] is a complex neurological disorder characterized by episodes of moderate-to-severe headache, most often unilateral and generally associated with nausea, and light and sound sensitivity.[3][4] Other characterizing symptoms may include vomiting, cognitive dysfunction, allodynia, and dizziness.[3] Exacerbation or worsening of headache symptoms during physical activity is another distinguishing feature.[5]

Up to one-third of people with migraine experience aura, a premonitory period of sensory disturbance widely accepted to be caused by cortical spreading depression at the onset of a migraine attack.[4] Although primarily considered to be a headache disorder, migraine is highly heterogenous in its clinical presentation and is better thought of as a spectrum disease rather than a distinct clinical entity.[6] Disease burden can range from episodic discrete attacks to chronic disease.[6][7]

Migraine is believed to be caused by a mixture of environmental and genetic factors that influence the excitation and inhibition of nerve cells in the brain.[8] The accepted hypothesis suggests that multiple primary neuronal impairments lead to a series of intracranial and extracranial changes, triggering a physiological cascade that leads to migraine symptomatology.[9]

Initial recommended treatment for acute attacks is with over-the-counter analgesics (pain medication) such as ibuprofen and paracetamol (acetaminophen) for headache, antiemetics (anti-nausea medication) for nausea, and the avoidance of migraine triggers.[10] Specific medications such as triptans, ergotamines, or calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist (CGRP) inhibitors may be used in those experiencing headaches that do not respond to the over-the-counter pain medications.[11] For people who experience four or more attacks per month, or could otherwise benefit from prevention, prophylactic medication is recommended.[12] Commonly prescribed prophylactic medications include beta blockers like propranolol, anticonvulsants like sodium valproate, antidepressants like amitriptyline, and other off-label classes of medications.[13] Preventive medications inhibit migraine pathophysiology through various mechanisms, such as blocking calcium and sodium channels, blocking gap junctions, and inhibiting matrix metalloproteinases, among other mechanisms.[14][15] Non-pharmacological preventive therapies include nutritional supplementation, dietary interventions, sleep improvement, and aerobic exercise.[16] In 2018, the first medication (Erenumab) of a new class of drugs specifically designed for migraine prevention called calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonists (CGRPs) was approved by the FDA.[17] As of July 2023, the FDA has approved eight drugs that act on the CGRP system for use in the treatment of migraine.[18]

Globally, approximately 15% of people are affected by migraine.[19] In the Global Burden of Disease Study, conducted in 2010, migraine ranked as the third-most prevalent disorder in the world.[20] It most often starts at puberty and is worst during middle age.[21] As of 2016[update], it is one of the most common causes of disability.[22]

Migraine typically presents with self-limited, recurrent severe headaches associated with autonomic symptoms.[23][24] About 15–30% of people living with migraine experience episodes with aura,[10][25] and they also frequently experience episodes without aura.[26] The severity of the pain, duration of the headache, and frequency of attacks are variable.[23] A migraine attack lasting longer than 72 hours is termed status migrainosus.[27] There are four possible phases to a migraine attack, although not all the phases are necessarily experienced:[28]

Migraine is associated with major depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, and obsessive–compulsive disorder. These psychiatric disorders are approximately 2–5 times more common in people without aura, and 3–10 times more common in people with aura.[29]

Prodromal or premonitory symptoms occur in about 60% of those with migraine,[30][31] with an onset that can range from two hours to two days before the start of pain or the aura.[32] These symptoms may include a wide variety of phenomena,[33] including altered mood, irritability, depression or euphoria, fatigue, craving for certain food(s), stiff muscles (especially in the neck), constipation or diarrhea, and sensitivity to smells or noise.[31] This may occur in those with either migraine with aura or migraine without aura.[34] Neuroimaging indicates the limbic system and hypothalamus as the origin of prodromal symptoms in migraine.[35]

|

|

|

|

Aura is a transient focal neurological phenomenon that occurs before or during the headache.[30] Aura appears gradually over a number of minutes (usually occurring over 5–60 minutes) and generally lasts less than 60 minutes.[36][37] Symptoms can be visual, sensory or motoric in nature, and many people experience more than one.[38] Visual effects occur most frequently: they occur in up to 99% of cases, and in more than 50% of cases are not accompanied by sensory or motor effects.[38] If any symptom remains after 60 minutes, the state is known as persistent aura.[39]

Visual disturbances often consist of a scintillating scotoma (an area of partial alteration in the field of vision which flickers and may interfere with a person's ability to read or drive).[30] These typically start near the center of vision and then spread out to the sides with zigzagging lines, which have been described as looking like fortifications or walls of a castle.[38] Usually, the lines are in black and white, but some people also see colored lines.[38] Some people lose part of their field of vision known as hemianopsia while others experience blurring.[38]

Sensory auras are the second most common type; they occur in 30–40% of people with auras.[38] Often, a feeling of pins-and-needles begins on one side in the hand and arm and spreads to the nose–mouth area on the same side.[38] Numbness usually occurs after the tingling has passed with a loss of position sense.[38] Other symptoms of the aura phase can include speech or language disturbances, world spinning, and, less commonly, motor problems.[38] Motor symptoms indicate that this is a hemiplegic migraine, and weakness often lasts longer than one hour unlike other auras.[38] Auditory hallucinations or delusions have also been described.[40]

Classically the headache is unilateral, throbbing, and moderate to severe in intensity.[36] It usually comes on gradually[36] and is aggravated by physical activity during a migraine attack.[28] However, the effects of physical activity on migraine are complex, and some researchers have concluded that, while exercise can trigger migraine attacks, regular exercise may have a prophylactic effect and decrease frequency of attacks.[41] The feeling of pulsating pain is not in phase with the pulse.[42] In more than 40% of cases, however, the pain may be bilateral (both sides of the head), and neck pain is commonly associated with it.[43] Bilateral pain is particularly common in those who have migraine without aura.[30] Less commonly pain may occur primarily in the back or top of the head.[30] The pain usually lasts 4 to 72 hours in adults;[36] however, in young children frequently lasts less than 1 hour.[44] The frequency of attacks is variable, from a few in a lifetime to several a week, with the average being about one a month.[45][46]

The pain is frequently accompanied by nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to light, sensitivity to sound, sensitivity to smells, fatigue, and irritability.[30] Many thus seek a dark and quiet room.[47] In a basilar migraine, a migraine with neurological symptoms related to the brain stem or with neurological symptoms on both sides of the body,[48] common effects include a sense of the world spinning, light-headedness, and confusion.[30] Nausea occurs in almost 90% of people, and vomiting occurs in about one-third.[47] Other symptoms may include blurred vision, nasal stuffiness, diarrhea, frequent urination, pallor, or sweating.[49] Swelling or tenderness of the scalp may occur as can neck stiffness.[49] Associated symptoms are less common in the elderly.[50]

Sometimes, aura occurs without a subsequent headache.[38] This is known in modern classification as a typical aura without headache, or acephalgic migraine in previous classification, or commonly as a silent migraine.[51][52] However, silent migraine can still produce debilitating symptoms, with visual disturbance, vision loss in half of both eyes, alterations in color perception, and other sensory problems, like sensitivity to light, sound, and odors.[53] It can last from 15 to 30 minutes, usually no longer than 60 minutes, and it can recur or appear as an isolated event.[54] Many report a sore feeling in the area where the migraine was, and some report impaired thinking for a few days after the headache has passed. The person may feel tired or "hung over" and have head pain, cognitive difficulties, gastrointestinal symptoms, mood changes, and weakness.[55] According to one summary, "Some people feel unusually refreshed or euphoric after an attack, whereas others note depression and malaise."[56][unreliable medical source?]

The underlying cause of migraine is unknown.[57] However, it is believed to be related to a mix of environmental and genetic factors.[8] Migraine runs in families in about two-thirds of cases[23] and rarely occur due to a single gene defect.[58] While migraine attacks were once believed to be more common in those of high intelligence, this does not appear to be true.[45] A number of psychological conditions are associated, including depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder.[59]

Success of the surgical migraine treatment by decompression of extracranial sensory nerves adjacent to vessels[60] suggests that people with migraine may have anatomical predisposition for neurovascular compression[61] that may be caused by both intracranial and extracranial vasodilation due to migraine triggers.[62] This, along with the existence of numerous cranial neural interconnections,[63] may explain the multiple cranial nerve involvement and consequent diversity of migraine symptoms.[64]

Studies of twins indicate a 34–51% genetic influence on the likelihood of developing migraine.[8] This genetic relationship is stronger for migraine with aura than for migraine without aura.[26] It is clear from family and populations studies that migraine is a complex disorder, where numerous genetic risk variants exist, and where each variant increases the risk of migraine marginally.[65][66] It is also known that having several of these risk variants increases the risk by a small to moderate amount.[58]

Single gene disorders that result in migraine are rare.[58] One of these is known as familial hemiplegic migraine, a type of migraine with aura, which is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion.[67][68] Four genes have been shown to be involved in familial hemiplegic migraine.[69] Three of these genes are involved in ion transport.[69] The fourth is the axonal protein PRRT2, associated with the exocytosis complex.[69] Another genetic disorder associated with migraine is CADASIL syndrome or cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy.[30] One meta-analysis found a protective effect from angiotensin converting enzyme polymorphisms on migraine.[70] The TRPM8 gene, which codes for a cation channel, has been linked to migraine.[71]

The common forms of migraine are polygenetic, where common variants of numerous genes contribute to the predisposition for migraine. These genes can be placed in three categories, increasing the risk of migraine in general, specifically migraine with aura, or migraine without aura.[72][73] Three of these genes, CALCA, CALCB, and HTR1F are already target for migraine specific treatments. Five genes are specific risk to migraine with aura, PALMD, ABO, LRRK2, CACNA1A and PRRT2, and 13 genes are specific to migraine without aura. Using the accumulated genetic risk of the common variations, into a so-called polygenetic risk, it is possible to assess e.g. the treatment response to triptans.[74][75]

Migraine may be induced by triggers, with some reporting it as an influence in a minority of cases[23] and others, the majority.[76] Many things, such as fatigue, certain foods, alcohol, and weather, have been labeled as triggers; however, the strength and significance of these relationships are uncertain.[76][77] Most people with migraine report experiencing triggers.[78] Symptoms may start up to 24 hours after a trigger.[23]

Also, evidence shows a strong association between migraine and the quality of sleep, particularly poor subjective quality of sleep. The relationship seems to be bidirectional, as migraine frequency increases with low quality of sleep, yet the underlying mechanism of this correlation remains poorly understood.[79]

Common triggers quoted are stress, hunger, and fatigue (these equally contribute to tension headaches).[76] Psychological stress has been reported as a factor by 50–80% of people.[80] Migraine has also been associated with post-traumatic stress disorder and abuse.[81] Migraine episodes are more likely to occur around menstruation.[80] Other hormonal influences, such as menarche, oral contraceptive use, pregnancy, perimenopause, and menopause, also play a role.[82] These hormonal influences seem to play a greater role in migraine without aura.[45] Migraine episodes typically do not occur during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, or following menopause.[30]

Between 12% and 60% of people report foods as triggers.[83][84]

There are many reports[85][86][87][88][89] that tyramine – which is naturally present in chocolate, alcoholic beverages, most cheeses, processed meats, and other foods – can trigger migraine symptoms in some individuals. Monosodium glutamate (MSG) has been reported as a trigger for migraine,[90] but a systematic review concluded that "a causal relationship between MSG and headache has not been proven... It would seem premature to conclude that the MSG present in food causes headache".[91]

Migraines may be triggered by weather changes, including changes in temperature and barometric pressure.[92][93]

A 2009 review on potential triggers in the indoor and outdoor environment previously concluded that while there were insufficient studies to confirm environmental factors as causing migraine, "migraineurs worldwide consistently report similar environmental triggers ... such as barometric pressure change, bright sunlight, flickering lights, air quality and odors".[94]

Migraine is believed to be primarily a neurological disorder,[95][96] while others believe it to be a neurovascular disorder with blood vessels playing the key role, although evidence does not support this completely.[97][98][99][100] Others believe both are likely important.[101][102][103][104] One theory is related to increased excitability of the cerebral cortex and abnormal control of pain neurons in the trigeminal nucleus of the brainstem.[105]

Sensitization of trigeminal pathways is a key pathophysiological phenomenon in migraine. It is debatable whether sensitization starts in the periphery or in the brain.[106][107]

Cortical spreading depression, or spreading depression according to Leão, is a burst of neuronal activity followed by a period of inactivity, which is seen in those with migraine with aura.[108] There are several explanations for its occurrence, including activation of NMDA receptors leading to calcium entering the cell.[108] After the burst of activity, the blood flow to the cerebral cortex in the affected area is decreased for two to six hours.[108] It is believed that when depolarization travels down the underside of the brain, nerves that sense pain in the head and neck are triggered.[108]

The exact mechanism of the head pain which occurs during a migraine episode is unknown.[109] Some evidence supports a primary role for central nervous system structures (such as the brainstem and diencephalon),[110] while other data support the role of peripheral activation (such as via the sensory nerves that surround blood vessels of the head and neck).[109] The potential candidate vessels include dural arteries, pial arteries and extracranial arteries such as those of the scalp.[109] The role of vasodilatation of the extracranial arteries, in particular, is believed to be significant.[111]

Adenosine, a neuromodulator, may be involved.[112] Released after the progressive cleavage of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), adenosine acts on adenosine receptors to put the body and brain in a low activity state by dilating blood vessels and slowing the heart rate, such as before and during the early stages of sleep. Adenosine levels are high during migraine attacks.[112][113] Caffeine's role as an inhibitor of adenosine may explain its effect in reducing migraine.[114] Low levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin, also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), are also believed to be involved.[115]

Calcitonin gene-related peptides (CGRPs) have been found to play a role in the pathogenesis of the pain associated with migraine, as levels of it become elevated during an attack.[10][42]

The diagnosis of a migraine is based on signs and symptoms.[23] Neuroimaging tests are not necessary to diagnose migraine, but may be used to find other causes of headaches in those whose examination and history do not confirm a migraine diagnosis.[116] It is believed that a substantial number of people with the condition remain undiagnosed.[23]

The diagnosis of migraine without aura, according to the International Headache Society, can be made according to the "5, 4, 3, 2, 1 criteria", which is as follows:[28]

If someone experiences two of the following: photophobia, nausea, or inability to work or study for a day, the diagnosis is more likely.[117] In those with four out of five of the following: pulsating headache, duration of 4–72 hours, pain on one side of the head, nausea, or symptoms that interfere with the person's life, the probability that this is a migraine attack is 92%.[10] In those with fewer than three of these symptoms, the probability is 17%.[10]

Migraine was first comprehensively classified in 1988.[26]

The International Headache Society updated their classification of headaches in 2004.[28] A third version was published in 2018.[118] According to this classification, migraine is a primary headache disorder along with tension-type headaches and cluster headaches, among others.[119]

Migraine is divided into six subclasses (some of which include further subdivisions):[120]

The diagnosis of abdominal migraine is controversial.[122] Some evidence indicates that recurrent episodes of abdominal pain in the absence of a headache may be a type of migraine[122][123] or are at least a precursor to migraine attacks.[26] These episodes of pain may or may not follow a migraine-like prodrome and typically last minutes to hours.[122] They often occur in those with either a personal or family history of typical migraine.[122] Other syndromes that are believed to be precursors include cyclical vomiting syndrome and benign paroxysmal vertigo of childhood.[26]

Other conditions that can cause similar symptoms to a migraine headache include temporal arteritis, cluster headaches, acute glaucoma, meningitis and subarachnoid hemorrhage.[10] Temporal arteritis typically occurs in people over 50 years old and presents with tenderness over the temple, cluster headache presents with one-sided nose stuffiness, tears and severe pain around the orbits, acute glaucoma is associated with vision problems, meningitis with fevers, and subarachnoid hemorrhage with a very fast onset.[10] Tension headaches typically occur on both sides, are not pounding, and are less disabling.[10]

Those with stable headaches that meet criteria for migraine should not receive neuroimaging to look for other intracranial disease.[124][125][126] This requires that other concerning findings such as papilledema (swelling of the optic disc) are not present. People with migraine are not at an increased risk of having another cause for severe headaches.[citation needed]

Management of migraine includes prevention of migraine attacks and rescue treatment. There are three main aspects of treatment: trigger avoidance, acute (abortive), and preventive (prophylactic) control.[127]

Modern approaches to migraine management emphasize personalized care that considers individual patient needs. Lifestyle modifications, such as managing triggers and addressing comorbidities, form the foundation of treatment. Behavioral techniques and supplements like magnesium and riboflavin can serve as supportive options for some individuals.[128] Behavioral techniques that have been utilized in the treatment of migraines include Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), relaxation training, biofeedback, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), as well as mindfulness-based therapies.[129] A 2024 systematic literature review and meta analysis found evidence that treatments such as CBT, relaxation training, ACT, and mindfulness-based therapies can reduce migraine frequency both on their own and in combination with other treatment options.[129] In addition, it was found that relaxation therapy aided in the lessening of migraine frequency when compared to education by itself.[129] Similarly, for children and adolescents, CBT and biofeedback strategies are effective in decreasing of frequency and intensity of migraines. These techniques often include relaxation methods and promotion of long-term management without medication side effects, which is emphasized for younger individuals.[129] Acute treatments, including NSAIDs and triptans, are most effective when administered early in an attack, while preventive medications are recommended for those experiencing frequent or severe migraines. Proven preventive options include beta blockers, topiramate, and CGRP inhibitors like erenumab and galcanezumab, which have demonstrated significant efficacy in clinical studies.[130] The European Consensus Statement provides a framework for diagnosis and management, emphasizing the importance of accurate assessment, patient education, and consistent adherence to prescribed treatments. Innovative therapies of oral medications used to treat migraine symptoms, such as gepants and ditans, are emerging as alternatives for patients who cannot use traditional options.[131]

A 2024 systematic review and network meta analysis compared the effectiveness of medications for acute migraine attacks in adults. It found that triptans were the most effective class of drugs, followed by non-steroidal anti-inflammatories. Gepants were less effective than non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.[132][133]

Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is a neuropeptide implicated in the pathophysiology of migraines. It is predominantly found in the trigeminal ganglion and central nervous system pathways associated with migraine mechanisms.[134] During migraine attacks, elevated levels of CGRP are detected, leading to vasodilation of cerebral and dural blood vessels and the release of inflammatory mediators from mast cells. These actions contribute to the transmission of nociceptive signals, culminating in migraine pain. Targeting CGRP has emerged as a promising therapeutic strategy for migraine management.[medical citation needed]

"Migraine exists on a continuum of different attack frequencies and associated levels of disability."[135] For those with occasional, episodic migraine, a "proper combination of drugs for prevention and treatment of migraine attacks" can limit the disease's impact on patients' personal and professional lives.[136] But fewer than half of people with migraine seek medical care and more than half go undiagnosed and undertreated.[137] "Responsive prevention and treatment of migraine is incredibly important" because evidence shows "an increased sensitivity after each successive attack, eventually leading to chronic daily migraine in some individuals."[136] Repeated migraine results in "reorganization of brain circuitry", causing "profound functional as well as structural changes in the brain."[138] "One of the most important problems in clinical migraine is the progression from an intermittent, self-limited inconvenience to a life-changing disorder of chronic pain, sensory amplification, and autonomic and affective disruption. This progression, sometimes termed chronification in the migraine literature, is common, affecting 3% of migraineurs in a given year, such that 8% of migraineurs have chronic migraine in any given year." Brain imagery reveals that the electrophysiological changes seen during an attack become permanent in people with chronic migraine; "thus, from an electrophysiological point of view, chronic migraine indeed resembles a never-ending migraine attack."[138] Severe migraine ranks in the highest category of disability, according to the World Health Organization, which uses objective metrics to determine disability burden for the authoritative annual Global Burden of Disease report. The report classifies severe migraine alongside severe depression, active psychosis, quadriplegia, and terminal-stage cancer.[139]

Migraine with aura appears to be a risk factor for ischemic stroke[140] doubling the risk.[141] Being a young adult, being female, using hormonal birth control, and smoking further increases this risk.[140] There also appears to be an association with cervical artery dissection.[142] Migraine without aura does not appear to be a factor.[143] The relationship with heart problems is inconclusive with a single study supporting an association.[140] Migraine does not appear to increase the risk of death from stroke or heart disease.[144] Preventative therapy of migraine in those with migraine with aura may prevent associated strokes.[145] People with migraine, particularly women, may develop higher than average numbers of white matter brain lesions of unclear significance.[146]

Migraine is common, with around 33% of women and 18% of men affected at some point in their lifetime.[147] Onset can be at any age, but prevalence rises sharply around puberty, and remains high until declining after age 50.[147] Before puberty, boys and girls are equally impacted, with around 5% of children experiencing migraine attacks. From puberty onwards, women experience migraine attacks at greater rates than men. From age 30 to 50, up to 4 times as many women experience migraine attacks as men;[147] this is most pronounced in migraine without aura.[148]

Worldwide, migraine affects nearly 15% or approximately one billion people.[19] In the United States, about 6% of men and 18% of women experience a migraine attack in a given year, with a lifetime risk of about 18% and 43%, respectively.[23] In Europe, migraine affects 12–28% of people at some point in their lives, with about 6–15% of adult men and 14–35% of adult women getting at least one attack yearly.[149] Rates of migraine are slightly lower in Asia and Africa than in Western countries.[45][150] Chronic migraine occurs in approximately 1.4–2.2% of the population.[151]

During perimenopause symptoms often get worse before decreasing in severity.[152] While symptoms resolve in about two-thirds of the elderly, in 3–10% they persist.[50]

An early description consistent with migraine is contained in the Ebers Papyrus, written around 1500 BCE in ancient Egypt.[153]

The word migraine is from the Greek ἡμικρᾱνίᾱ (hēmikrāníā), 'pain in half of the head',[154] from ἡμι- (hēmi-), 'half' and κρᾱνίον (krāníon), 'skull'.[155]

In 200 BCE, writings from the Hippocratic school of medicine described the visual aura that can precede the headache and a partial relief occurring through vomiting.[156]

A second-century description by Aretaeus of Cappadocia divided headaches into three types: cephalalgia, cephalea, and heterocrania.[157] Galen of Pergamon used the term hemicrania (half-head), from which the word migraine was eventually derived.[157] Galen also proposed that the pain arose from the meninges and blood vessels of the head.[156] Migraine was first divided into the two now used types – migraine with aura (migraine ophthalmique) and migraine without aura (migraine vulgaire) in 1887 by Louis Hyacinthe Thomas, a French librarian.[156] The mystical visions of Hildegard von Bingen, which she described as "reflections of the living light", are consistent with the visual aura experienced during migraine attacks.[158]

Trepanation, the deliberate drilling of holes into a skull, was practiced as early as 7,000 BCE.[153] While sometimes people survived, many would have died from the procedure due to infection.[159] It was believed to work via "letting evil spirits escape".[160] William Harvey recommended trepanation as a treatment for migraine in the 17th century.[161] The association between trepanation and headaches in ancient history may simply be a myth or unfounded speculation that originated several centuries later. In 1913, the world-famous American physician William Osler misinterpreted the French anthropologist and physician Paul Broca's words about a set of children's skulls from the Neolithic age that he found during the 1870s. These skulls presented no evident signs of fractures that could justify this complex surgery for mere medical reasons. Trepanation was probably born of superstitions, to remove "confined demons" inside the head, or to create healing or fortune talismans with the bone fragments removed from the skulls of the patients. However, Osler wanted to make Broca's theory more palatable to his modern audiences, and explained that trepanation procedures were used for mild conditions such as "infantile convulsions headache and various cerebral diseases believed to be caused by confined demons."[162]

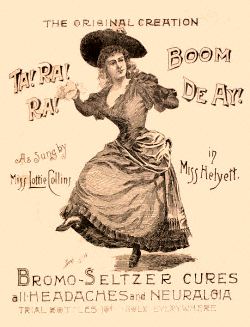

While many treatments for migraine have been attempted, it was not until 1868 that use of a substance which eventually turned out to be effective began.[156] This substance was the fungus ergot from which ergotamine was isolated in 1918[163] and first used to treat migraine in 1925.[164] Methysergide was developed in 1959 and the first triptan, sumatriptan, was developed in 1988.[163] During the 20th century, with better study design, effective preventive measures were found and confirmed.[156]

Migraine is a significant source of both medical costs and lost productivity. It has been estimated that migraine is the most costly neurological disorder in the European Community, costing more than €27 billion per year.[165] In the United States, direct costs have been estimated at $17 billion, while indirect costs – such as missed or decreased ability to work – is estimated at $15 billion.[166] Nearly a tenth of the direct cost is due to the cost of triptans.[166] In those who do attend work during a migraine attack, effectiveness is decreased by around a third.[165] Negative impacts also frequently occur for a person's family.[165]

Transcranial magnetic stimulation shows promise,[10][167] as does transcutaneous supraorbital nerve stimulation.[168] There is preliminary evidence that a ketogenic diet may help prevent episodic and long-term migraine.[169][170]

Statistical data indicates that women may be more prone to having migraine, showing migraine incidence three times higher among women than men.[171][172] The Society for Women's Health Research has also mentioned hormonal influences, mainly estrogen, as having a considerable role in provoking migraine pain. Studies and research related to the sex dependencies of migraine are ongoing, and conclusions have yet to be achieved.[173]

Disability classes for the Global Burden of Disease study (table 8)

| External audio | |

|---|---|

| Headache | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cephalalgia |

|

|

| Person with a headache | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Types | Tension headache, cluster headache, sinusitis, migraine headache, hangover headache, cold-stimulus headache (brain freeze) |

| Treatment | Over-the-counter painkillers, sleep, drinking water, eating food, head or neck massage |

A headache, also known as cephalalgia, is the symptom of pain in the face, head, or neck. It can occur as a migraine, tension-type headache, or cluster headache.[1][2] There is an increased risk of depression in those with severe headaches.[3]

Headaches can occur as a result of many conditions. There are a number of different classification systems for headaches. The most well-recognized is that of the International Headache Society, which classifies it into more than 150 types of primary and secondary headaches. Causes of headaches may include dehydration; fatigue; sleep deprivation; stress;[4] the effects of medications (overuse) and recreational drugs, including withdrawal; viral infections; loud noises; head injury; rapid ingestion of a very cold food or beverage; and dental or sinus issues (such as sinusitis).[5]

Treatment of a headache depends on the underlying cause, but commonly involves pain medication (especially in case of migraine or cluster headaches).[6] A headache is one of the most commonly experienced of all physical discomforts.[7]

About half of adults have a headache in a given year.[3] Tension headaches are the most common,[7] affecting about 1.6 billion people (21.8% of the population) followed by migraine headaches which affect about 848 million (11.7%).[8]

There are more than 200 types of headaches. Some are harmless and some are life-threatening. The description of the headache and findings on neurological examination, determine whether additional tests are needed and what treatment is best.[9]

Headaches are broadly classified as "primary" or "secondary".[10] Primary headaches are benign, recurrent headaches not caused by underlying disease or structural problems. For example, migraine is a type of primary headache. While primary headaches may cause significant daily pain and disability, they are not dangerous from a physiological point of view. Secondary headaches are caused by an underlying disease, like an infection, head injury, vascular disorders, brain bleed, stomach irritation, or tumors. Secondary headaches can be dangerous. Certain "red flags" or warning signs indicate a secondary headache may be dangerous.[11]

Ninety percent of all headaches are primary headaches.[12] Primary headaches usually first start when people are between 20 and 40 years old.[13][14] The most common types of primary headaches are migraines and tension-type headaches.[14] They have different characteristics. Migraines typically present with pulsing head pain, nausea, photophobia (sensitivity to light) and phonophobia (sensitivity to sound).[15] Tension-type headaches usually present with non-pulsing "bandlike" pressure on both sides of the head, not accompanied by other symptoms.[16][17] Such kind of headaches may be further classified into-episodic and chronic tension type headaches[18] Other very rare types of primary headaches include:[11]

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021)

|

Headaches may be caused by problems elsewhere in the head or neck. Some of these are not harmful, such as cervicogenic headache (pain arising from the neck muscles). The excessive use of painkillers can paradoxically cause worsening painkiller headaches.[9][19]

More serious causes of secondary headaches include the following:[11]

Gastrointestinal disorders may cause headaches, including Helicobacter pylori infection, celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, gastroparesis, and hepatobiliary disorders.[20][21][22] The treatment of the gastrointestinal disorders may lead to a remission or improvement of headaches.[22]

Migraine headaches are also associated with Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome (CVS). CVS is characterized by episodes of severe vomiting, and often occur alongside symptoms similar to those of migraine headaches (photophobia, abdominal pain, etc.).[23]

The brain itself is not sensitive to pain, because it lacks pain receptors. However, several areas of the head and neck do have pain receptors and can thus sense pain. These include the extracranial arteries, middle meningeal artery, large veins, venous sinuses, cranial and spinal nerves, head and neck muscles, the meninges, falx cerebri, parts of the brainstem, eyes, ears, teeth, and lining of the mouth.[24][25] Pial arteries, rather than pial veins are responsible for pain production.[11]

Headaches often result from traction or irritation of the meninges and blood vessels.[26] The pain receptors may be stimulated by head trauma or tumours and cause headaches. Blood vessel spasms, dilated blood vessels, inflammation or infection of meninges and muscular tension can also stimulate pain receptors.[25] Once stimulated, a nociceptor sends a message up the length of the nerve fibre to the nerve cells in the brain, signalling that a part of the body hurts.[27]

Primary headaches are more difficult to understand than secondary headaches. The exact mechanisms which cause migraines, tension headaches and cluster headaches are not known.[28] There have been different hypotheses over time that attempt to explain what happens in the brain to cause these headaches.[29]

Migraines are currently thought to be caused by dysfunction of the nerves in the brain.[30] Previously, migraines were thought to be caused by a primary problem with the blood vessels in the brain.[31] This vascular theory, which was developed in the 20th century by Wolff, suggested that the aura in migraines is caused by constriction of intracranial vessels (vessels inside the brain), and the headache itself is caused by rebound dilation of extracranial vessels (vessels just outside the brain). Dilation of these extracranial blood vessels activates the pain receptors in the surrounding nerves, causing a headache. The vascular theory is no longer accepted.[30][32] Studies have shown migraine head pain is not accompanied by extracranial vasodilation, but rather only has some mild intracranial vasodilation.[33]

Currently, most specialists think migraines are due to a primary problem with the nerves in the brain.[30] Auras are thought to be caused by a wave of increased activity of neurons in the cerebral cortex (a part of the brain) known as cortical spreading depression[34] followed by a period of depressed activity.[35] Some people think headaches are caused by the activation of sensory nerves which release peptides or serotonin, causing inflammation in arteries, dura and meninges and also cause some vasodilation. Triptans, medications that treat migraines, block serotonin receptors and constrict blood vessels.[36]

People who are more susceptible to experiencing migraines without headaches are those who have a family history of migraines, women, and women who are experiencing hormonal changes or are taking birth control pills or are prescribed hormone replacement therapy.[37]

Tension headaches are thought to be caused by the activation of peripheral nerves in the head and neck muscles.[38]

Cluster headaches involve overactivation of the trigeminal nerve and hypothalamus in the brain, but the exact cause is unknown.[28][39]

| Tension headache | New daily persistent headache | Cluster headache | Migraine |

|---|---|---|---|

| mild to moderate dull or aching pain | severe pain | moderate to severe pain | |

| duration of 30 minutes to several hours | duration of at least four hours daily | duration of 30 minutes to 3 hours | duration of 4 hours to 3 days |

| Occur in periods of 15 days a month for three months | may happen multiple times in a day for months | periodic occurrence; several per month to several per year | |

| located as tightness or pressure across head | located on one or both sides of the head | located one side of head focused at eye or temple | located on one or both sides of head |

| consistent pain | pain describable as sharp or stabbing | pulsating or throbbing pain | |

| no nausea or vomiting | nausea, perhaps with vomiting | ||

| no aura | no aura | auras | |

| uncommonly, light sensitivity or noise sensitivity | may be accompanied by running nose, tears, and drooping eyelid, often only on one side | sensitivity to movement, light, and noise | |

| exacerbated by regular use of acetaminophen or NSAIDS | may exist with tension headache[40] |

Most headaches can be diagnosed by the clinical history alone.[11] If the symptoms described by the person sound dangerous, further testing with neuroimaging or lumbar puncture may be necessary. Electroencephalography (EEG) is not useful for headache diagnosis.[41]

The first step to diagnosing a headache is to determine if the headache is old or new.[42] A "new headache" can be a headache that has started recently, or a chronic headache that has changed character.[42] For example, if a person has chronic weekly headaches with pressure on both sides of his head, and then develops a sudden severe throbbing headache on one side of his head, they have a new headache.[citation needed]

It can be challenging to differentiate between low-risk, benign headaches and high-risk, dangerous headaches since symptoms are often similar.[43] Headaches that are possibly dangerous require further lab tests and imaging to diagnose.[14]

The American College for Emergency Physicians published criteria for low-risk headaches. They are as follows:[44]

A number of characteristics make it more likely that the headache is due to potentially dangerous secondary causes which may be life-threatening or cause long-term damage. These "red flag" symptoms mean that a headache warrants further investigation with neuroimaging and lab tests.[14]

In general, people complaining of their "first" or "worst" headache warrant imaging and further workup.[14] People with progressively worsening headache also warrant imaging, as they may have a mass or a bleed that is gradually growing, pressing on surrounding structures and causing worsening pain.[43] People with neurological findings on exam, such as weakness, also need further workup.[43]

The American Headache Society recommends using "SSNOOP", a mnemonic to remember the red flags for identifying a secondary headache:[42]

Other red flag symptoms include:[14][42][43][45]

| Red Flag | Possible causes | The reason why a red flag indicates possible causes | Diagnostic tests |

|---|---|---|---|

| New headache after age 50 | Temporal arteritis, mass in brain | Temporal arteritis is an inflammation of vessels close to the temples in older people, which decreases blood flow to the brain and causes pain. May also have tenderness in temples or jaw claudication. Some brain cancers are more common in older people. | Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (diagnostic test for temporal arteritis), neuroimaging |

| Very sudden onset headache (thunderclap headache) | Brain bleed (subarachnoid hemorrhage, hemorrhage into mass lesion, vascular malformation), pituitary apoplexy, mass (especially in posterior fossa) | A bleed in the brain irritates the meninges which causes pain. Pituitary apoplexy (bleeding or impaired blood supply to the pituitary gland at the base of the brain) is often accompanied by double vision or visual field defects, since the pituitary gland is right next to the optic chiasm (eye nerves). | Neuroimaging, lumbar puncture if computed tomography is negative |

| Headaches increasing in frequency and severity | Mass, subdural hematoma, medication overuse | As a brain mass gets larger, or a subdural hematoma (blood outside the vessels underneath the dura) it pushes more on surrounding structures causing pain. Medication overuse headaches worsen with more medication taken over time. | Neuroimaging, drug screen |

| New onset headache in a person with possible HIV or cancer | Meningitis (chronic or carcinomatous), brain abscess including toxoplasmosis, metastasis | People with HIV or cancer are immunosuppressed so are likely to get infections of the meninges or infections in the brain causing abscesses. Cancer can metastasize, or travel through the blood or lymph to other sites in the body. | Neuroimaging, lumbar puncture if neuroimaging is negative |

| Headache with signs of total body illness (fever, stiff neck, rash) | Meningitis, encephalitis (inflammation of the brain tissue), Lyme disease, collagen vascular disease | A stiff neck, or inability to flex the neck due to pain, indicates inflammation of the meninges. Other signs of systemic illness indicates infection. | Neuroimaging, lumbar puncture, serology (diagnostic blood tests for infections) |

| Papilledema | Brain mass, benign intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri), meningitis | Increased intracranial pressure pushes on the eyes (from inside the brain) and causes papilledema. | Neuroimaging, lumbar puncture |

| Severe headache following head trauma | Brain bleeds (intracranial hemorrhage, subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma), post-traumatic headache | Trauma can cause bleeding in the brain or shake the nerves, causing a post-traumatic headache | Neuroimaging of brain, skull, and possibly cervical spine |

| Inability to move a limb | Arteriovenous malformation, collagen vascular disease, intracranial mass lesion | Focal neurological signs indicate something is pushing against nerves in the brain responsible for one part of the body | Neuroimaging, blood tests for collagen vascular diseases |

| Change in personality, consciousness, or mental status | Central nervous system infection, intracranial bleed, mass | Change in mental status indicates a global infection or inflammation of the brain, or a large bleed compressing the brainstem where the consciousness centers lie | Blood tests, lumbar puncture, neuroimaging |

| Headache triggered by cough, exertion or while engaged in sexual intercourse | Mass lesion, subarachnoid hemorrhage | Coughing and exertion increases the intra cranial pressure, which may cause a vessel to burst, causing a subarachnoid hemorrhage. A mass lesion already increases intracranial pressure, so an additional increase in intracranial pressure from coughing etc. will cause pain. | Neuroimaging, lumbar puncture |

Old headaches are usually primary headaches and are not dangerous. They are most often caused by migraines or tension headaches. Migraines are often unilateral, pulsing headaches accompanied by nausea or vomiting. There may be an aura (visual symptoms, numbness or tingling) 30–60 minutes before the headache, warning the person of a headache. Migraines may also not have auras.[45] Tension-type headaches usually have bilateral "bandlike" pressure on both sides of the head usually without nausea or vomiting. However, some symptoms from both headache groups may overlap. It is important to distinguish between the two because the treatments are different.[45]

The mnemonic 'POUND' helps distinguish between migraines and tension-type headaches. POUND stands for:

One review article found that if 4–5 of the POUND characteristics are present, a migraine is 24 times as likely a diagnosis than a tension-type headache (likelihood ratio 24). If 3 characteristics of POUND are present, migraine is 3 times more likely a diagnosis than tension type headache (likelihood ratio 3).[17] If only 2 POUND characteristics are present, tension-type headaches are 60% more likely (likelihood ratio 0.41). Another study found the following factors independently each increase the chance of migraine over tension-type headache: nausea, photophobia, phonophobia, exacerbation by physical activity, unilateral, throbbing quality, chocolate as a headache trigger, and cheese as a headache trigger.[47]

Cluster headaches are relatively rare (1 in 1000 people) and are more common in men than women.[48] They present with sudden onset explosive pain around one eye and are accompanied by autonomic symptoms (tearing, runny nose and red eye).[11]

Temporomandibular jaw pain (chronic pain in the jaw joint), and cervicogenic headache (headache caused by pain in muscles of the neck) are also possible diagnoses.[42]

For chronic, unexplained headaches, keeping a headache diary can be useful for tracking symptoms and identifying triggers, such as association with menstrual cycle, exercise and food. While mobile electronic diaries for smartphones are becoming increasingly common, a recent review found most are developed with a lack of evidence base and scientific expertise.[49]

Cephalalgiaphobia is fear of headaches or getting a headache.

New headaches are more likely to be dangerous secondary headaches. They can, however, simply be the first presentation of a chronic headache syndrome, like migraine or a tension headache.

One recommended diagnostic approach is as follows.[50] If any urgent red flags are present such as visual impairment, new seizures, new weakness, or new confusion, further workup with imaging and possibly a lumbar puncture should be done (see red flags section for more details). If the headache is sudden onset (thunderclap headache), a computed tomography scan (CT scan) to look for a brain bleed (subarachnoid hemorrhage) should be done. If the CT scan does not show a bleed, a lumbar puncture should be done to look for blood in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), as the CT scan can be falsely negative and subarachnoid hemorrhages can be fatal. If there are signs of infection such as fever, rash, or stiff neck, a lumbar puncture to look for meningitis should be considered. In an older person, if there is jaw claudication and scalp tenderness, a temporal artery biopsy should be performed to look for temporal arteritis, immediate treatment should be started, if results of the biopsy are positive.[citation needed]

The US Headache Consortium has guidelines for neuroimaging of non-acute headaches.[51] Most old, chronic headaches do not require neuroimaging. If a person has the characteristic symptoms of a migraine, neuroimaging is not needed as it is very unlikely the person has an intracranial abnormality.[52] If the person has neurological findings, such as weakness, on exam, neuroimaging may be considered.[citation needed]

All people who present with red flags indicating a dangerous secondary headache should receive neuroimaging.[45] The best form of neuroimaging for these headaches is controversial.[14] Non-contrast computerized tomography (CT) scan is usually the first step in head imaging as it is readily available in Emergency Departments and hospitals and is cheaper than MRI. Non-contrast CT is best for identifying an acute head bleed. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is best for brain tumors and problems in the posterior fossa, or back of the brain.[14] MRI is more sensitive for identifying intracranial problems, however it can pick up brain abnormalities that are not relevant to the person's headaches.[14]

The American College of Radiology recommends the following imaging tests for different specific situations:[53]

| Clinical Features | Recommended neuroimaging test |

|---|---|

| Headache in immunocompromised people (cancer, HIV) | MRI of head with or without contrast |

| Headache in people older than 60 with suspected temporal arteritis | MRI of head with or without contrast |

| Headache with suspected meningitis | CT or MRI without contrast |

| Severe headache in pregnancy | CT or MRI without contrast |

| Severe unilateral headache caused by possible dissection of carotid or arterial arteries | MRI of head with or without contrast, magnetic resonance angiography or Computed Tomography Angiography of head and neck. |

| Sudden onset headache or worst headache of life | CT of head without contrast, Computed Tomography Angiography of head and neck with contrast, magnetic resonance angiography of head and neck with and without contrast, MRI of head without contrast |

A lumbar puncture is a procedure in which cerebral spinal fluid is removed from the spine with a needle. A lumbar puncture is necessary to look for infection or blood in the spinal fluid. A lumbar puncture can also evaluate the pressure in the spinal column, which can be useful for people with idiopathic intracranial hypertension (usually young, obese women who have increased intracranial pressure), or other causes of increased intracranial pressure. In most cases, a CT scan should be done first.[11]

Headaches are most thoroughly classified by the International Headache Society's International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD), which published the second edition in 2004.[54] The third edition of the International Headache Classification was published in 2013 in a beta version ahead of the final version.[55] This classification is accepted by the WHO.[56]

Other classification systems exist. One of the first published attempts was in 1951.[57] The US National Institutes of Health developed a classification system in 1962.[58]

The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) is an in-depth hierarchical classification of headaches published by the International Headache Society. It contains explicit (operational) diagnostic criteria for headache disorders. The first version of the classification, ICHD-1, was published in 1988. The current revision, ICHD-2, was published in 2004.[59] The classification uses numeric codes. The top, one-digit diagnostic level includes 14 headache groups. The first four of these are classified as primary headaches, groups 5-12 as secondary headaches, cranial neuralgia, central and primary facial pain and other headaches for the last two groups.[60]

The ICHD-2 classification defines migraines, tension-types headaches, cluster headache and other trigeminal autonomic headache as the main types of primary headaches.[54] Also, according to the same classification, stabbing headaches and headaches due to cough, exertion and sexual activity (sexual headache) are classified as primary headaches. The daily-persistent headaches along with the hypnic headache and thunderclap headaches are considered primary headaches as well.[61][62]

Secondary headaches are classified based on their cause and not on their symptoms.[54] According to the ICHD-2 classification, the main types of secondary headaches include those that are due to head or neck trauma such as whiplash injury, intracranial hematoma, post craniotomy or other head or neck injury. Headaches caused by cranial or cervical vascular disorders such as ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack, non-traumatic intracranial hemorrhage, vascular malformations or arteritis are also defined as secondary headaches. This type of headache may also be caused by cerebral venous thrombosis or different intracranial vascular disorders. Other secondary headaches are those due to intracranial disorders that are not vascular such as low or high pressure of the cerebrospinal fluid pressure, non-infectious inflammatory disease, intracranial neoplasm, epileptic seizure or other types of disorders or diseases that are intracranial but that are not associated with the vasculature of the central nervous system.[citation needed]

ICHD-2 classifies headaches that are caused by the ingestion of a certain substance or by its withdrawal as secondary headaches as well. This type of headache may result from the overuse of some medications or exposure to some substances. HIV/AIDS, intracranial infections and systemic infections may also cause secondary headaches. The ICHD-2 system of classification includes the headaches associated with homeostasis disorders in the category of secondary headaches. This means that headaches caused by dialysis, high blood pressure, hypothyroidism, cephalalgia and even fasting are considered secondary headaches. Secondary headaches, according to the same classification system, can also be due to the injury of any of the facial structures including teeth, jaws, or temporomandibular joint. Headaches caused by psychiatric disorders such as somatization or psychotic disorders are also classified as secondary headaches.[citation needed]

The ICHD-2 classification puts cranial neuralgias and other types of neuralgia in a different category. According to this system, there are 19 types of neuralgias and headaches due to different central causes of facial pain. Moreover, the ICHD-2 includes a category that contains all the headaches that cannot be classified.[citation needed]

Although the ICHD-2 is the most complete headache classification there is and it includes frequency in the diagnostic criteria of some types of headaches (primarily primary headaches), it does not specifically code frequency or severity which are left at the discretion of the examiner.[54]

The NIH classification consists of brief definitions of a limited number of headaches.[63]

The NIH system of classification is more succinct and only describes five categories of headaches. In this case, primary headaches are those that do not show organic or structural causes. According to this classification, primary headaches can only be vascular, myogenic, cervicogenic, traction, and inflammatory.[64]

Primary headache syndromes have many different possible treatments. In those with chronic headaches the long term use of opioids appears to result in greater harm than benefit.[65]

Treatment of secondary headaches involves treating their underlying cause. For example, a person with meningitis will require antibiotics, and a person with a brain tumor may require surgery, chemotherapy or brain radiation. The possible origins of a headache have been studied and classified.

Migraine can be somewhat improved by lifestyle changes, but most people require medicines to control their symptoms.[11] Medications are either to prevent getting migraines, or to reduce symptoms once a migraine starts.[citation needed]

Preventive medications are generally recommended when people have more than four attacks of migraine per month, headaches last longer than 12 hours or the headaches are very disabling.[11][66] Possible therapies include beta blockers, antidepressants, anticonvulsants and NSAIDs.[66] The type of preventive medicine is usually chosen based on the other symptoms the person has. For example, if the person also has depression, an antidepressant is a good choice.[citation needed]

Abortive therapies for migraines may be oral, if the migraine is mild to moderate, or may require stronger medicine given intravenously or intramuscularly. Mild to moderate headaches should first be treated with acetaminophen (paracetamol) or NSAIDs, like ibuprofen. If accompanied by nausea or vomiting, an antiemetic such as metoclopramide (Reglan) can be given orally or rectally. Moderate to severe attacks should be treated first with an oral triptan, a medication that mimics serotonin (an agonist) and causes mild vasoconstriction. If accompanied by nausea and vomiting, parenteral (through a needle in the skin) triptans and antiemetics can be given.[67]

Sphenopalatine ganglion block (SPG block, also known nasal ganglion block or pterygopalatine ganglion blocks) can abort and prevent migraines, tension headaches and cluster headaches. It was originally described by American ENT surgeon Greenfield Sluder in 1908. Both blocks and neurostimulation have been studied as treatment for headaches.[68]

Several complementary and alternative strategies can help with migraines. The American Academy of Neurology guidelines for migraine treatment in 2000 stated relaxation training, electromyographic feedback and cognitive behavioral therapy may be considered for migraine treatment, along with medications.[69]

Tension-type headaches can usually be managed with NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen, aspirin), or acetaminophen.[11] Triptans are not helpful in tension-type headaches unless the person also has migraines. For chronic tension type headaches, amitriptyline is the only medication proven to help.[11][70][71] Amitriptyline is a medication which treats depression and also independently treats pain. It works by blocking the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, and also reduces muscle tenderness by a separate mechanism.[70] Studies evaluating acupuncture for tension-type headaches have been mixed.[72][73][74][75][76] Overall, they show that acupuncture is probably not helpful for tension-type headaches.

Abortive therapy for cluster headaches includes subcutaneous sumatriptan (injected under the skin) and triptan nasal sprays. High flow oxygen therapy also helps with relief.[11]

For people with extended periods of cluster headaches, preventive therapy can be necessary. Verapamil is recommended as first line treatment. Lithium can also be useful. For people with shorter bouts, a short course of prednisone (10 days) can be helpful. Ergotamine is useful if given 1–2 hours before an attack.[11]

Peripheral neuromodulation has tentative benefits in primary headaches including cluster headaches and chronic migraine.[77] How it may work is still being looked into.[77]

Literature reviews find that approximately 64–77% of adults have had a headache at some point in their lives.[78][79] During each year, on average, 46–53% of people have headaches.[78][79] However, the prevalence of headache varies widely depending on how the survey was conducted, with studies finding lifetime prevalence of as low as 8% to as high as 96%.[78][79][80] Most of these headaches are not dangerous. Only approximately 1–5% of people who seek emergency treatment for headaches have a serious underlying cause.[81]

More than 90% of headaches are primary headaches.[82] Most of these primary headaches are tension headaches.[79] Most people with tension headaches have "episodic" tension headaches that come and go. Only 3.3% of adults have chronic tension headaches, with headaches for more than 15 days in a month.[79]

Approximately 12–18% of people in the world have migraines.[79] More women than men experience migraines. In Europe and North America, 5–9% of men experience migraines, while 12–25% of women experience migraines.[78]

Cluster headaches are relatively uncommon. They affect only 1–3 per thousand people in the world. Cluster headaches affect approximately three times as many men as women.[79]

The first recorded classification system was published by Aretaeus of Cappadocia, a medical scholar of Greco-Roman antiquity. He made a distinction between three different types of headache: i) cephalalgia, by which he indicates a sudden onset, temporary headache; ii) cephalea, referring to a chronic type of headache; and iii) heterocrania, a paroxysmal headache on one side of the head. Another classification system that resembles the modern ones was published by Thomas Willis, in De Cephalalgia in 1672. In 1787 Christian Baur generally divided headaches into idiopathic (primary headaches) and symptomatic (secondary ones), and defined 84 categories.[63]

In general, children experience the same types of headaches as adults do, but their symptoms may be slightly different. The diagnostic approach to headaches in children is similar to that of adults. However, young children may not be able to verbalize pain well.[83] If a young child is fussy, they may have a headache.[84]

Approximately 1% of emergency department visits for children are for headache.[85][86] Most of these headaches are not dangerous. The most common type of headache seen in pediatric emergency rooms is headache caused by a cold (28.5%). Other headaches diagnosed in the emergency department include post-traumatic headache (20%), headache related to a problem with a ventriculoperitoneal shunt (a device put into the brain to remove excess CSF and reduce pressure in the brain) (11.5%) and migraine (8.5%).[86][87] The most common serious headaches found in children include brain bleeds (subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma), brain abscesses, meningitis and ventriculoperitoneal shunt malfunction. Only 4–6.9% of kids with a headache have a serious cause.[84]

Just as in adults, most headaches are benign, but when head pain is accompanied with other symptoms such as speech problems, muscle weakness, and loss of vision, a more serious underlying cause may exist: hydrocephalus, meningitis, encephalitis, abscess, hemorrhage, tumor, blood clots, or head trauma. In these cases, the headache evaluation may include CT scan or MRI in order to look for possible structural disorders of the central nervous system.[88] If a child with a recurrent headache has a normal physical exam, neuroimaging is not recommended. Guidelines state children with abnormal neurologic exams, confusion, seizures and recent onset of worst headache of life, change in headache type or anything suggesting neurologic problems should receive neuroimaging.[84]

When children complain of headaches, many parents are concerned about a brain tumor. Generally, headaches caused by brain masses are incapacitating and accompanied by vomiting.[84] One study found characteristics associated with brain tumor in children are: headache for greater than 6 months, headache related to sleep, vomiting, confusion, no visual symptoms, no family history of migraine and abnormal neurologic exam.[89]

Some measures can help prevent headaches in children. Drinking plenty of water throughout the day, avoiding caffeine, getting enough and regular sleep, eating balanced meals at the proper times, and reducing stress and excess of activities may prevent headaches.[90] Treatments for children are similar to those for adults, however certain medications such as narcotics should not be given to children.[84]

Children who have headaches will not necessarily have headaches as adults. In one study of 100 children with headache, eight years later 44% of those with tension headache and 28% of those with migraines were headache free.[91] In another study of people with chronic daily headache, 75% did not have chronic daily headaches two years later, and 88% did not have chronic daily headaches eight years later.[92]